On 17 June the Nazi German command made the decision to break the totalitarian Alliance formed in 1939. In the early hours of 22 June 1941, a deafening barrage marked the beginning of Nazi Germany’s boldest military campaign of the Second World War. At approximately 3:15 am, German forces crossed the Soviet border, turning against their former ally and launching Operation Barbarossa — the largest invasion in the history of warfare.

The plan was ambitious: a swift, decisive blitzkrieg designed to annihilate the Red Army and push German troops as far as the Archangel-Astrakhan line. Hitler’s forces — bolstered by allies from Finland, Romania, Slovakia, Hungary, and Italy — numbered nearly four million men, supported by 4,000 tanks and a similar number of aircraft. The invasion force was divided into three main Army Groups: North, Centre and South, each with a specific strategic target.

Despite being taken by surprise, the Soviet Union was not unprepared. The Red Army initially fielded over three million soldiers, with mobilisation quickly swelling its ranks to around 5.5 million. The USSR held a significant advantage regarding raw firepower: over 15,000 tanks and 10,000 aircraft were at its disposal, far outmatching German numbers.

As the German war machine prepared to unleash Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, the eastern front was divided into three vast military formations — Army Groups North, Centre, and South — each with a specific strategic goal and massive resources at its disposal.

From its staging grounds in East Prussia, Army Group North was tasked with conquering the Soviet Baltic republics and capturing Leningrad, home to the Soviet Baltic Fleet’s principal naval base. Under its command were the 16th and 18th field armies, as well as the 4th Panzer Group. Altogether, this force comprised 23 infantry divisions, three armoured divisions, and three motorised divisions. Air support came in the form of the 1st Air Fleet, which fielded roughly 1,070 aircraft.

Stationed to the east and north-east of Warsaw, Army Group Centre was the most heavily armoured of the three formations. It spearheaded the thrust towards Moscow, the political and symbolic heart of the Soviet Union. This group consisted of the 4th and 9th field armies, along with the 2nd and 3rd Panzer Groups. In total, it deployed 34 infantry divisions, nine panzer divisions, six motorised divisions, a cavalry division, and two additional motorised brigades. The 2nd and 8th Air Fleets provided an aerial complement of around 1,670 aircraft.

Stretching to the Black Sea, Army Group South was responsible for securing Ukraine and the fertile lands beyond. It was the largest in terms of manpower, but its ranks were bolstered significantly by allied — though less capable — formations from Romania and Hungary.

The Hungarian Corps and Romania’s 3rd and 4th Armies were poorly equipped, inadequately trained, and inexperienced in fast-paced mechanised warfare.

The main German ground elements included the 6th, 11th, and 17th armies, with the 1st Panzer Group providing mobile strength. Air support came from the Romanian air force and Germany’s 4th Air Fleet. All told, Army Group South boasted 48 infantry divisions, five panzer divisions, four motorised divisions, six infantry brigades, three motorised brigades, four cavalry brigades, and roughly 1,300 aircraft.

Meanwhile, the German High Command held 24 reserve divisions in the Reich, including two panzer and one motorised division, ready to be deployed as needed.

In the summer of 1941, the Red Army was undergoing extensive reorganisation. After an inconclusive and costly campaign against Finland, Soviet military planners began a sweeping modernisation effort. The aim was to create a modern, mobile force capable of launching swift mechanised strikes — a „blitzkrieg of their own.”

However, when the German invasion began, many Soviet border units were still operating under peacetime conditions, with numerous formations understrength. The corps remained the Soviet Union’s key organisational unit. A typical army comprised two infantry corps (each containing three infantry divisions) and one mechanised corps (made up of two tank brigades and one motorised brigade).

While Soviet tank brigades matched German regiments in numbers, they lacked critical support elements such as artillery and logistics. Soviet air power — theoretically formidable — was largely obliterated within the first 24 hours of the invasion and played little role in the initial defence.

Facing the joint German-Finnish northern thrust were three Soviet armies stationed along the Finnish border. The 14th Army guarded Murmansk, the 7th held the front stretching to Lake Ladoga, and the 23rd defended the narrow Karelian Isthmus.

Opposing Army Group North and the northern flank of Army Group Centre was the Soviet Northwestern Front, comprising the 8th and 11th armies, with the 27th Army held in reserve.

Further south, the Western Front defended the area around the Białystok salient with the 3rd, 4th, and 10th armies. However, their positions — deep inside the protruding salient — made them vulnerable to encirclement.

On the southern flank, two major Soviet formations awaited the German onslaught: the Southwestern and Southern Fronts. The Southwestern Front, deployed from the Kovel region down to the Romanian border, included the 5th, 6th, 12th, and 26th armies. Below them, the 9th and 18th armies of the Southern Front guarded the Black Sea coast and the strategically crucial port city of Odessa — a vital hub for the Soviet Black Sea Fleet.

The two adversaries could not have been more different in their military doctrines and equipment philosophy. The Wehrmacht emphasised precision engineering, coordination, and quality of matériel. The Red Army, on the other hand, pursued mass production and numerical superiority — often at the expense of reliability and training.

As the stage was set in June 1941, the eastern front resembled a vast chessboard, with millions of troops, thousands of tanks and aircraft poised to collide in what would become the most brutal theatre of the Second World War.

In the opening months, the Wehrmacht appeared unstoppable. Army Group North advanced rapidly, reaching the outskirts of Leningrad by August. The resulting siege would drag on for nearly 900 days, ultimately failing. To the south, Kiev fell, and German forces pushed deeper into Ukraine. Army Group Centre drove relentlessly toward Moscow, bringing the German war machine to the Soviet capital’s doorstep by late 1941.

But it was at Moscow that Hitler’s grand design unravelled. As the brutal Russian winter set in and supply lines stretched thin, the Red Army launched a ferocious counteroffensive. The German advance ground to a halt. Operation Barbarossa, conceived as a lightning strike, ended in stalemate and retreat — a turning point that signalled the beginning of Nazi Germany’s slow descent into defeat.

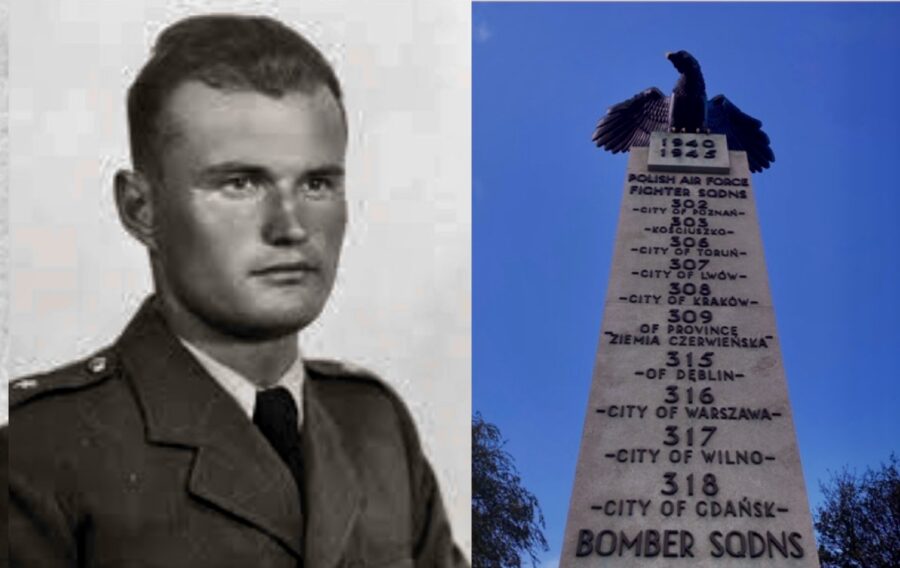

The German invasion also triggered a shift in political allegiances. Thousands of Poles who had been deported to Siberia under Stalin’s rule suddenly found themselves in a new position when the Sikorski–Mayski Agreement of July 1941 restored diplomatic ties between the Polish government-in-exile and the USSR. This paved the way for the formation of the Anders Army, a Polish military force that would eventually leave Soviet soil and fight alongside the Allies.

Despite these developments, life for ordinary Poles remained grim. The German occupation expanded to include the entirety of pre-war Polish territory, and Nazi policies of forced labor, displacement, and racial extermination intensified. The Holocaust escalated dramatically in the aftermath of Barbarossa, with ghettos liquidated and deportations to extermination camps such as Treblinka and Auschwitz increasing in frequency and scale.

Operation Barbarossa thus marked a crucial turning point for Poland in World War II—not as a move toward liberation, but as a deepening of its suffering. Poland became not only a battlefield but also the epicenter of German Nazi genocidal policy, with its people subjected to shifting brutalities from both the Nazi and Soviet regimes. The war, for Poles, was not just a conflict between powers—it was an ongoing catastrophe without safe haven.

Source: IPN, Dzieje.pl, Przystanek Historia

Photo: @Jan34733995

Tomasz Modrzejewski