On 22 January 1863, the January Uprising, the largest Polish national uprising of the 19th century, began with the Manifesto of the Provisional National Government, declaring „all sons of Poland are free and equal citizens without distinction of creed, condition or rank„. The uprising lasted almost 2 years but could not shake off the foreign yoke.

In 1863 the Polish society was torn between finding a way to coexist under the triple occupation of their country or to fight to regain independence.

Following Russia’s defeat in the Crimean War, the Poles hoped to regain independence or wide autonomy for the Kingdom of Poland. In the areas formerly belonging to the Republic, conspiratorial associations began to be organised, the participants of which undertook preparations for battle.

Two attitudes confronted in conspiratorial circles. The so-called ‘Red’ camp was in favour of launching an armed struggle for independence and called for a national uprising. The ‘White’ party, although also pro-independence oriented, opposed overly rapid plans for an uprising, promoting the idea of organic work and seeking for more autonomy and reform.

In June of 1860 and February 1861, patriotic manifestations in Warsaw were brutally suppressed by the Russian police.

Another patriotic demonstration organised on 8 April 1861 on Castle Square in Warsaw was the breaking point in the situation. The civilian gathering was bloodily suppressed by the Russian army, which used guns against the civilian population. At least 200 were killed and 500 wounded.

Russian tsarist governor Mikhail Gorchakov wrote to Tsar Alexander II: “The teaching has had a strong effect; everything is now quiet and trembling with fear.”

On 14 October 1861, the Russian authorities imposed martial law on the territory of the Kingdom of Poland. Troops bivouacked in the streets of Warsaw and cannons were rolled out.

In January 1862, the Russian Tsar decided to establish civil authorities in the Polish Kingdom. In defining the frames of the reforms he stated: “Neither a constitution nor a Polish army; no political autonomy; a large administrative autonomy”.

On 22 May 1862, Alexander II appointed his brother V. Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich as governor of the Kingdom of Poland, and a Polish aristocrat, Margrave Aleksander Wielopolski as head of the civil government.

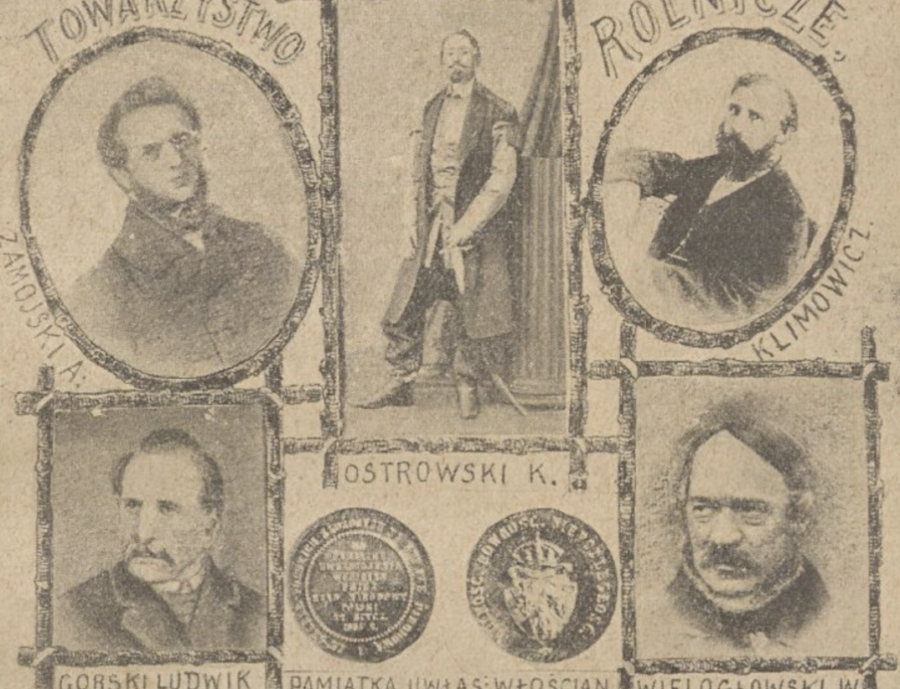

Wielopolski also seeks to destroy opposition to his loyalist views by disbanding the Polish Farmers Society on 6 April 1861 a group of aristocracy and nobility that owns large land estates and wants to spend money on patriotic and organic work.

On 8 April 1861, more than 100 people were killed and around 200 wounded when Russian soldiers fired on participants in a demonstration against the dissolution of the Agricultural Society at Castle Square in Warsaw.

Wielopolski, who presented a loyalist mindset, wanted to focus on reforms and minimise the possibility of a national uprising. Therefore while reforming the civil administration and improving the situation of the serfs he also pressed for a new conscription wave to the Russian imperial army.

The so-called Branka, a conscription phase, was this time supposed to be based on the lists of names of the conscripts – a move to disturb the work and development of secret patriotic organisations. It was a change in the custom in which the conscripts were selected with a special draw.

Unfortunately, the idea aimed at securing stability in the Kingdom backfired and created social anger.

The forced conscription started on the night of 14 and 15 January 1863. The following day, the National Central Committee declared Wielopolski “a great despicable criminal and traitor”.

On 22 January 1863, the Central National Committee issued a Manifesto proclaiming an uprising and appointing the Provisional National Government.

“The despicable invading government, enraged by the resistance of the victim it was tormenting, decided to deal it a decisive blow – to kidnap several tens of thousands of its bravest, most zealous defenders, clothe them in the hateful uniform of Moscow and drive them thousands of miles into eternal misery and perdition. The Polish youth has sworn to throw off the accursed yoke or die. So follow it, Polish nation, follow it! After the terrible disgrace of captivity, after the incomprehensible torments of oppression, the Central National Committee, now the only legitimate Government of your Nation, calls you to the field of the last battle, to the field of the glory of victory, which it will give you and, by the name of God in heaven, swear to give you,” said the manifesto.

Despite inadequate weaponry and small numbers, Polish insurgents attacked Russian outposts practically throughout the Kingdom of Poland.

Initially, Russia was terrified by possible intervention by the Western powers that it saw during the Crimean War. Contrary to both the press and public opinion, the UK and French governments limited themselves to diplomatic notes.

Historians claim that around 200,000 people served in the Polish forces. Despite initial success, the invading forces began to gain the upper hand. By the end of 1863, the total number of Russian troops fighting against the uprising reached 400,000.

The Polish forces were unable to motivate the peasants to participate in the Uprising. Their situation was also changed by the Tsar’s 1864 abolition of serfdom and partial enfranchisement.

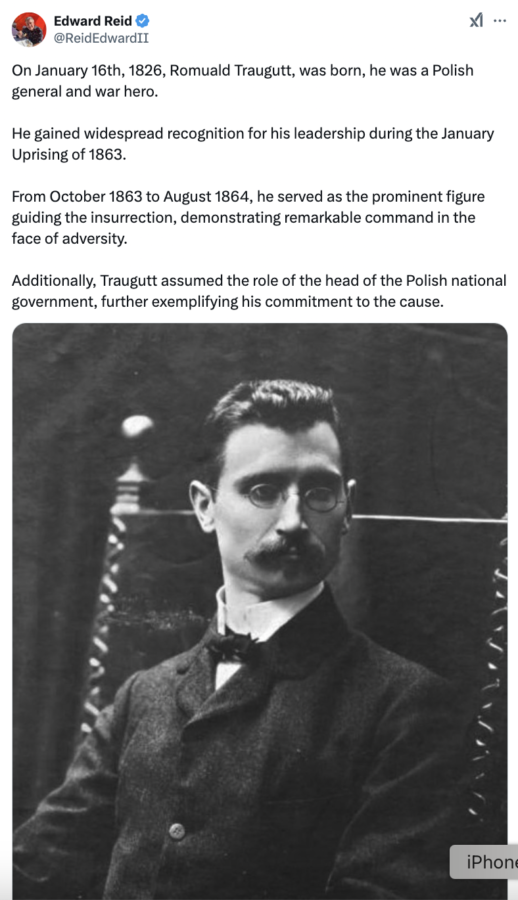

On the night of 10-11 April 1864, after a denunciation, the Russian police arrested Romuald Traugutt – the last dictator of the Uprising.

On 19 July 1864, a Russian military court sentenced him to death by hanging, along with other members of the National Government. The sentence was carried out on the slopes of the Warsaw Citadel on 5 August 1864 in the presence of 30,000 inhabitants of the Polish capital.

As a result of the uprising, the Tsarist administration sentenced some 669 people to death and deported 38,000 Poles to Siberia and other lands of the Russian Empire.

Source: Dzieje.pl

Photo: @DowOperSZ

Tomasz Modrzejewski