Poland has long been the underdog in Europe’s economic story now it is becoming its own benchmark. Recent commentary from German and Swiss media highlights how Poland is shifting roles: from cautious follower to rising model, especially in the eyes of its western neighbour. „Neue Zuercher Zeitung” reports Poland is ready to change its position in European economic competition for good.

For decades Germany regarded Poland through a paternal lens. The imagery was clear: Germany the strong growth engine; Poland the post-communist follower. That narrative, pointed out by the Swiss daily Neue Zürcher Zeitung, served German self-understanding long after the end of the Cold War.

Today the picture is changing. Germany’s engine of growth has slowed; Poland’s economy is picking up pace. At a Berlin economic forum, German-Polish engagement resulted in bold remarks from German business leaders. “We need more Warsaw in Berlin,” declared Philipp Hausmann of the German Eastern Economy Commission, a clear nod to Poland’s achievements.

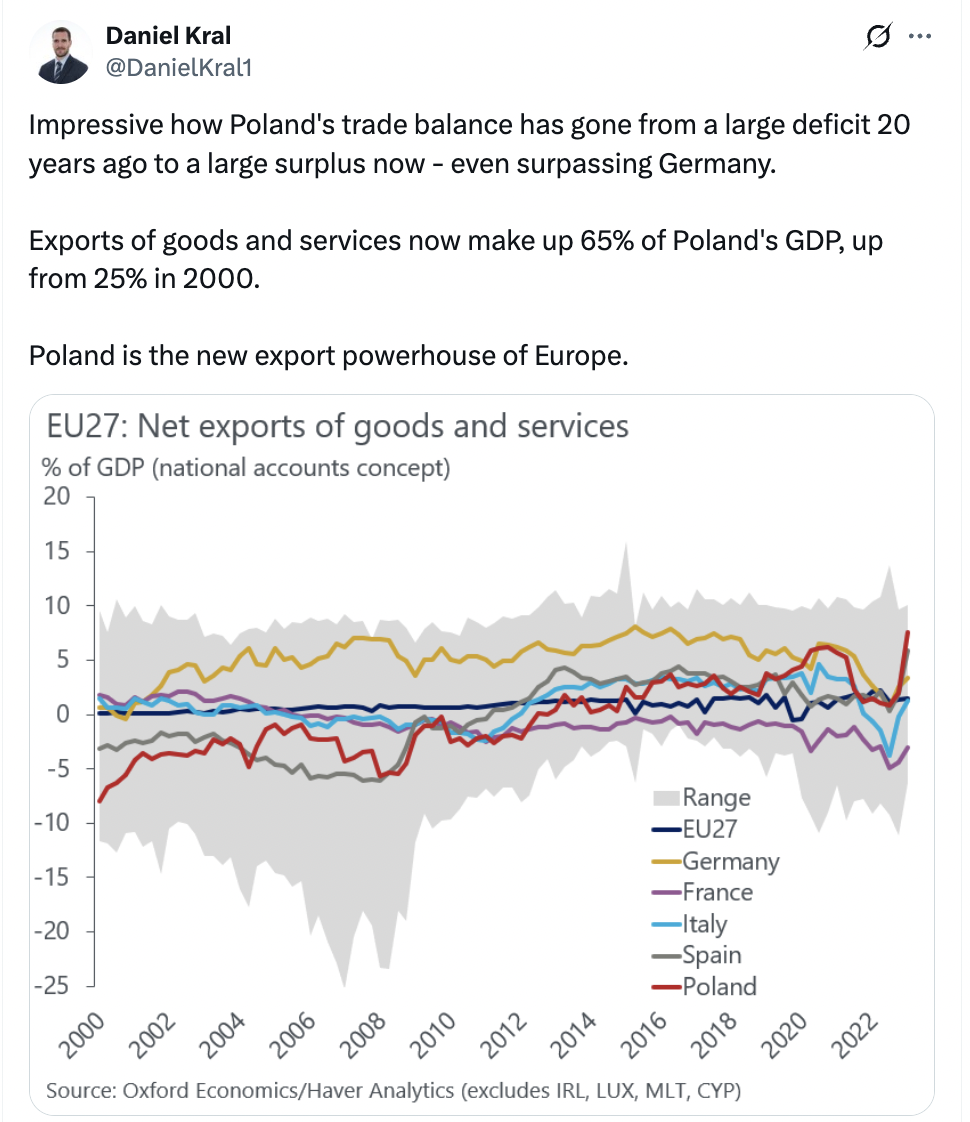

What is driving this change? Three factors stand out: strong growth, administrative digitalisation and confidence in cooperation. Poland has outpaced the European average for the last two years, with forecasts for around 3.3 % growth in the current year. Meanwhile Germany wrestles with structural headwinds. This divergence is prompting firms and investors alike to look at Poland differently.

The mObywatel app used by more than 10 million citizens is cited as an example of how Poland is leapfrogging into effective e-administration. The capacity for entrepreneurs to execute contracts online and streamline bureaucratic steps is portrayed as markedly less cumbersome than in Germany.

In bilateral business encounters, Polish partners are described as more self-assured than before. While political issues sometimes lead to friction, economic relationships remain pragmatic. For German firms, the shift is both strategic and psychological.

Yet challenges remain. Despite the progress, Poland’s GDP per capita is still only about 45 % of Germany’s, and around 70 % when adjusted for purchasing power. Germany holds deeper capital reservoirs and engineering expertise.

Poland faces rising wage pressures and a tightening labour market. What once was a cost-advantage is fading as competition for qualified personnel intensifies.

Germany has long treated Poland as a production base and a partner in its supply chains. Now that the relationship is being recalibrated. If Poland continues to ascend, it may become not just a partner but a benchmark. For German business and policy-makers, this shift raises questions: what can Germany learn? How can it adapt to the changing dynamic?

At one level, the lesson is simple: agility in modernising economy and governance matters. At another, it is humbling: Germany must recognise that growth models rooted in large-scale incumbents and heavy industry may no longer deliver the same pace. Poland’s rise is a wake-up call.

For Poland, the journey is far from finished. Sustaining growth, navigating demographic shifts and evolving from a cost-competitive base into a value-added economy will define the next decade. But the era when Poland was a follower appears to be ending. The question now is: what happens when Poland becomes the example others try to emulate, including Germany?

Although the Western media are praising Poland’s economic growth, mostly based on the GDP, the country remains behind in public records, especially in private wealth, innovation, and political importance.

Contrasts speak for themselves. Germany and Poland may share borders and history, yet their strategic capacities still belong to different categories.

Germany’s population stands at around 80 million, twice that of Poland’s 40 million. On the international stage, Germany sits among the world’s most influential powers, a member of the G7 and the European Union, while Poland remains an aspirant to the G20, reflecting its growing but still limited global presence.

The gap in economic output remains vast. Germany’s GDP of $4.3 trillion dwarfs Poland’s $860 billion. Average personal wealth tells a similar story: $113,000 per German citizen, compared with $17,000 per Pole. In exports, Germany moves goods worth $1.6 trillion annually, while Poland’s exports reach $380 billion, a success in its own right, but still only a fraction of its neighbour’s trade volume.

Germany’s financial sector ranks among Europe’s strongest, with five banks in the EU’s top 50; Poland has only one, at the bottom of the list. In the high-tech industry, Germany hosts three to four of Europe’s top ten firms, Poland none.

The research divide is even wider. Among the world’s most frequently cited scientists, 340 are German, none Polish. Between 2007 and 2024, Germany secured €5.2 billion in European Research Council grants for over 2,800 projects; Poland obtained €143 million for 83.

Germany’s influence inside the EU is extensive, from control over the European Parliament and European Commission leadership to a decisive voice in the European Central Bank and fiscal rules such as the schwarze Null (balanced-budget policy).

Poland, by contrast, remains underrepresented in Brussels’ bureaucratic ranks even below Hungary.

In 2022-23, the EU approved €72 billion in German state aid, amounting to over half of the entire bloc’s total; Poland’s public-aid figures were negligible.

Defence spending also reveals the gap. Germany allocates around 400 billion PLN annually to defence; Poland spends about 120 billion PLN. Germany has five defence companies among Europe’s top 15 and ranks fourth globally in arms exports. Poland has none in the top tier and ranks nineteenth worldwide.

Domestic production makes up 60–70 % of Germany’s military purchases, compared with 25–30 % in Poland. While Germany produces tanks, air-defence systems and submarines, Poland still struggles with the basics, even the production of gunpowder.

Since 2022, Germany has revised its security strategy, modernised logistics and debated the return of conscription. Poland, however, lacks an updated strategy and continues to rely on individual initiative; soldiers often equip themselves, civil defence is largely theoretical, and strategic transport routes, such as the Suwalki Gap rail line, remain underdeveloped.

Germany enjoys two layers of strategic buffers, including Poland itself and hosts the largest American military contingent in Europe, about 35,000 troops. Poland’s U.S. presence is smaller, roughly 10,000, many on rotation.

In NATO, Germany plays a decisive political role, at times blocking the accession of Ukraine and Georgia, while Poland remains largely a petitioner rather than a policy-maker.

Germany exerts a strong influence over Poland’s economy: German banks control around 9 % of assets in the Polish financial market, while Polish banks own none in Germany. Until recently, German media groups owned about 75 % of Poland’s press market; Poland has no equivalent presence in Germany.

German foundations and networks of influence operate actively in Poland, while the reverse is minimal.

The Frankfurt Stock Exchange has a capitalisation of $2.2 trillion; Warsaw’s totals $147 billion. In the automotive sector, Germany dominates: it is home to three of Europe’s top ten car manufacturers and five of the world’s leading subcontractors. Poland has none.

German airports occupy two places in Europe’s top ten for passenger traffic and three for air cargo, while Poland’s main hub ranks 39th.

German companies have invested €52 billion in Poland; Polish firms have invested just €6 billion in Germany.

The ambitions of national elites also differ sharply. German coalition agreements routinely express the desire to lead Europe; in Poland, political fragmentation and partisan warfare often undermine strategic continuity. Germany maintains a cross-party consensus on long-term projects such as Energiewende (energy transition) and Ostpolitik, while in Poland, institutional stability remains fragile.

Germany possesses the capacity to build reactors and enrich uranium, even after phasing out its nuclear plants. Poland, by contrast, has yet to construct its first. Germany participates in NATO’s nuclear-sharing programme; Poland does not, and any debate about nuclear weapons remains taboo.

The comparison underscores the scale of the challenge facing Poland if it hopes to match Germany’s strategic potential. While Warsaw has made extraordinary progress over the past three decades, Berlin still holds most of the cards in capital, influence, and scientific power.

Yet Poland’s momentum, demographic vitality and growing confidence could shift some of these balances in the future.

Source: NZZ, Money.pl

Photo: Faceboo/Go to Warsaw

Tomasz Modrzejewski