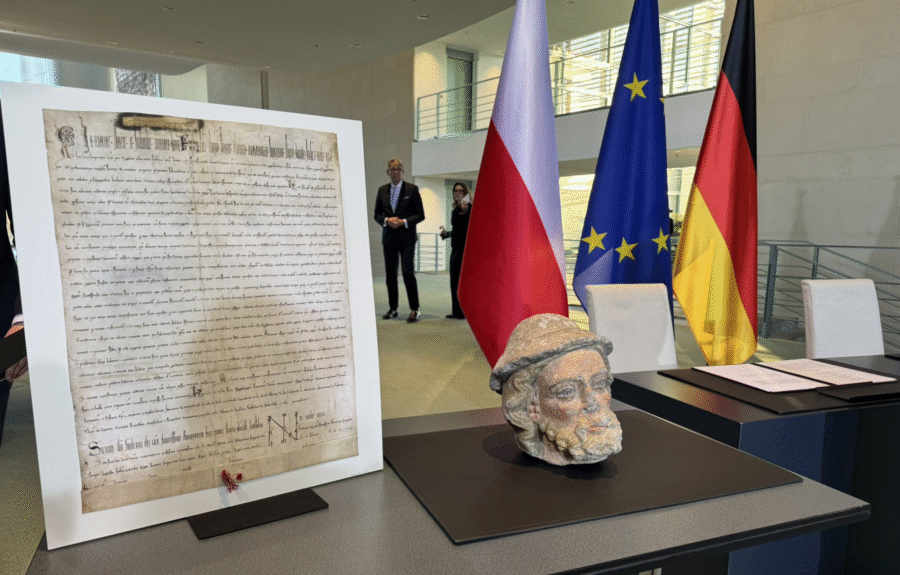

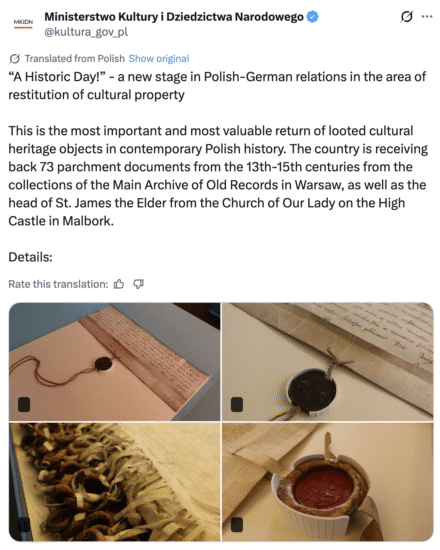

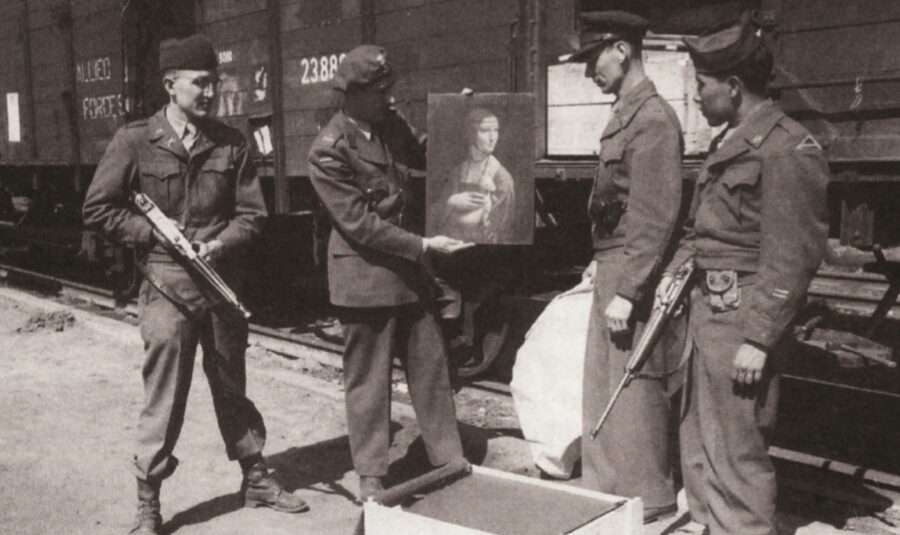

Poland has celebrated a landmark victory in its decades-long effort to reclaim cultural treasures looted by Germans during and after the Second World War. A trove of 73 medieval parchment documents and a rare 14th-century sculptural fragment have been formally returned from Germany, marking what officials describe as a turning point in cross-border heritage restitution.

The documents, once preserved in Warsaw’s Central Archives of Historical Records, and the carved head of St James the Greater originating from Malbork Castle’s Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, represent both scholarly and spiritual value. Their recovery underscores the scale of cultural losses inflicted on Poland throughout the 20th century.

Government representatives hailed the return as one of the most significant achievements since negotiations began in the aftermath of the war. Polish and German cultural authorities have now pledged closer cooperation to expedite further claims involving thousands of displaced artefacts still held unlawfully by Germany.

“During intergovernmental consultations with the participation of the German government, we recovered elements of our heritage for which we have been fighting for several decades. In my view, this is a historic breakthrough — the most important at least since 1989 — as it has taken place with the involvement of the authorities at the federal level. Thanks to this, the head of St James the Greater from Malbork Castle will return to Poland. This object was illegally removed in 1957 and subsequently sold to a German museum. We know that it belongs to the Polish state,” the head of the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage Marta Cienkowska told Rzeczpospolita.

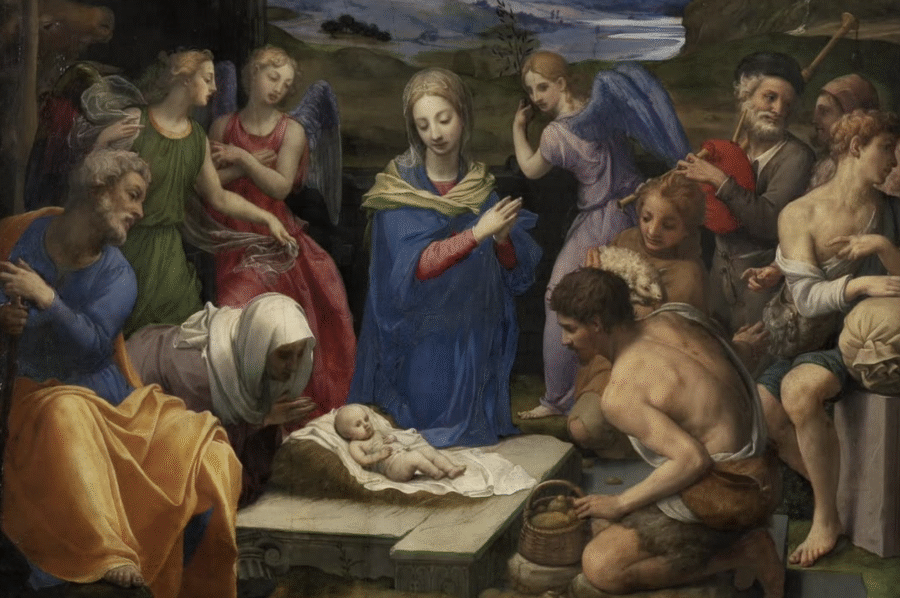

The head of St James the Greater, dated to around 1340, is a fragment of a Gothic sculpture that once adorned the southern wall of the Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Malbork Castle. It belonged to a gallery of figures set on consoles, shattered during the Red Army’s shelling of the castle in February 1945. The head was later stolen by a student and sold to the collection of a museum in Nuremberg.

The returned documents originally became part of the Crown Archives at Wawel after the creation of the secular Duchy of Prussia by Grand Master of the Teutonic Order Albrecht Hohenzollern, who pledged fealty to King Sigismund I the Old.

In the autumn of 1939, they were kept in the Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw before being transferred, at the turn of 1940 and 1941, to the Prussian State Archive in Königsberg, with one item being lost in the process.

They were later “evacuated” westward. Discovered in Goslar, Lower Saxony, they ultimately found their way to the Secret State Archives of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation.

Poland has sought their return since the war, filing a formal restitution request in November 2022, a move reiterated by the Polish ambassador in Berlin in October 2023. It has now been approved at the government level.

According to Rzeczpospolita, negotiations are also nearing completion regarding the potential return of a gold ring set with a diamond belonging to King Sigismund I the Old, once part of Princess Izabela Czartoryska’s renowned royal casket.

The ring was traced in the collection of the Jewellery Museum in Pforzheim, Baden-Württemberg, by Prof. Ewa Letkiewicz, an art historian from Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin. She published her research in The Art History Bulletin in 2007, reconstructing the object’s provenance and concluding that it entered the museum in 1963 along with 179 other historic rings formerly owned by collector Heinz Battke. Prof. Letkiewicz also discovered that in the early 21st century, the ring was briefly displayed in Częstochowa, twinned with the German city of Pforzheim.

For Poland, each recovered object is both an act of justice and a restoration of memory. As international attention to wartime cultural theft continues to grow, officials hope this milestone signals a wider shift towards accountability.

Photo: X/@kgrzadzielski

Tomasz Modrzejewski