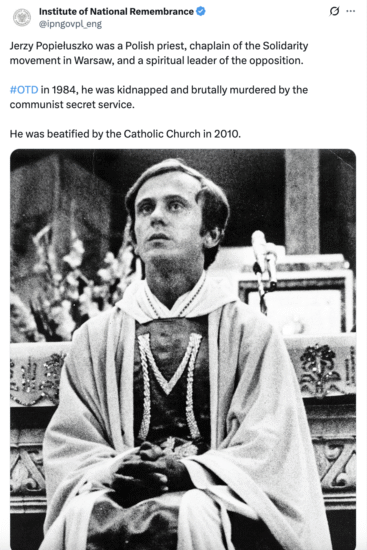

He was born Alfons Popiełuszko on 14 September 1947 in the small village of Okopy, near Suchowola, in north-eastern Poland. The son of devout farmers, Marianna and Władysław Popiełuszko, he grew up in a humble, deeply religious home that valued faith, work, and perseverance. In 1971, as a young seminarian, he officially changed his name to Jerzy, the name that would later echo through Polish history.

From an early age, Jerzy was close to the Church. He served as an altar boy at the parish in Suchowola. He later attended the local secondary school before joining the Archdiocesan Seminary of St John the Baptist in Warsaw in 1965. His studies were abruptly interrupted when, during his second year, he was conscripted into a special military unit for clerics in Bartoszyce, notorious for its harsh treatment of seminarians. Subjected to harassment and psychological torment, the young Popiełuszko returned from military service in fragile health but with unshaken faith.

In May 1972, he was ordained a priest by Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, Primate of Poland, in Warsaw’s St John’s Cathedral. His first pastoral post was in Ząbki, a suburb of Warsaw, where he quickly became known for his empathy and activism.

Over the following years, Popiełuszko served in several parishes, eventually moving in 1980 to St Stanislaus Kostka Church in Warsaw’s Żoliborz district, his final and most significant posting.

The summer of 1980, marked by strikes across Poland, brought Popiełuszko into contact with the Solidarity movement. When Warsaw’s steelworkers invited him to celebrate Mass during their strike on 31 August 1980, he entered the gates of the Huta Warszawa steelworks to applause.

“I thought someone important was walking behind me,” he later recalled. “But those were claps for the Church finally crossing the factory gates after thirty years.”

From that day, he became Solidarity’s chaplain, offering spiritual and moral support to workers, opposition figures, artists and intellectuals. His small parish flat became a meeting place for people from all walks of life, united by their desire for freedom and dignity.

When martial law was declared by the communist government of General Wojciech Jaruzelski on 13 December 1981, Father Jerzy’s defiance only deepened. Constantly watched and harassed by the Security Service (SB), he organised aid for imprisoned activists and their families, collected medicine and food, and secretly recorded political trials, smuggling the tapes to Radio Free Europe.

His so-called Masses for the Homeland, held monthly at St Stanislaus Kostka Church, drew thousands of worshipers, including non-Catholic members of the anti-communist movement. They were both religious ceremonies and moral rallies, inspiring hope amid oppression. His sermons, rooted in St Paul’s call to “overcome evil with good”, became a lifeline for a nation under brutal dictatorship.

“Understanding our geopolitical situation does not mean surrendering our rights as a nation,” he told worshippers.

But his growing influence infuriated the Communist authorities, who branded his services “anti-Communist rallies.” He was placed under surveillance, threatened, and subjected to provocation. In one incident, agents planted explosives and propaganda leaflets in his flat in an attempt to frame him.

Despite calls from Church leaders to send him abroad for safety, Father Jerzy refused to leave his parish. “A shepherd does not abandon his flock,” he reportedly said.

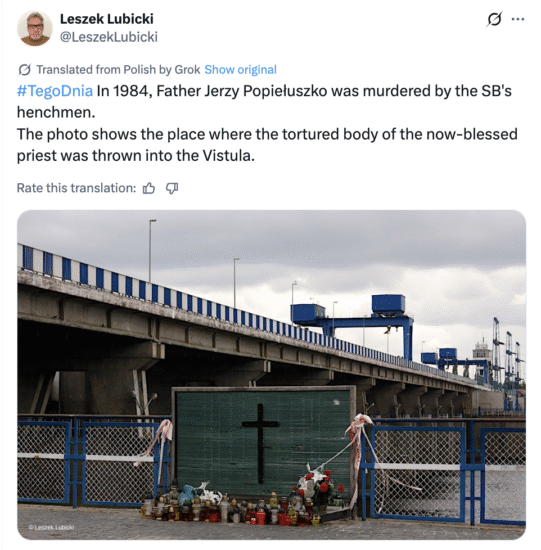

On 19 October 1984, after celebrating Mass in Bydgoszcz, Father Jerzy was abducted by three secret police officers, Grzegorz Piotrowski, Leszek Pękala and Waldemar Chmielewski. His driver, Waldemar Chrostowski, managed to escape and raise the alarm. The priest was beaten unconscious, bound, and thrown into the boot of a car. His captors later tied a sack of stones to his feet and dumped his body into the Vistula Reservoir near Włocławek.

When the mutilated body was recovered on 30 October 1984, the country was in shock. Nearly 800,000 mourners attended his funeral on 3 November, led by Primate Józef Glemp. Father Jerzy was buried beside his Żoliborz church, where his tomb quickly became a site of pilgrimage. Over the decades, more than 20 million people have prayed at his grave.

The trial of his killers revealed chilling details of state complicity, yet the full truth about who ordered the murder remains unknown. All four men convicted in connection with the crime were released early.

Despite the brutality of his death, Popiełuszko’s message of forgiveness and moral courage endured. In 1997, the Vatican opened its beatification process, and in 2009, Pope Benedict XVI signed the decree recognising him as a martyr. The following year, on 6 June 2010, his beatification Mass drew vast crowds to Piłsudski Square in Warsaw.

In France, a miraculous healing attributed to his intercession in the recovery of a man suffering from chronic leukaemia was later confirmed by the Church, paving the way for his canonisation, expected in the coming years.

Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko remains one of the most powerful symbols of moral resistance in modern Europe. His words, simple, steadfast and uncompromising, continue to resonate:

“To live in truth and conquer evil with good – this is the victory of freedom.”

For millions, he is not only the martyr of Solidarity, but the conscience of a nation that learned to stand upright even under tyranny.

Photo: @ZDzienniczka/X

Tomasz Modrzejewski