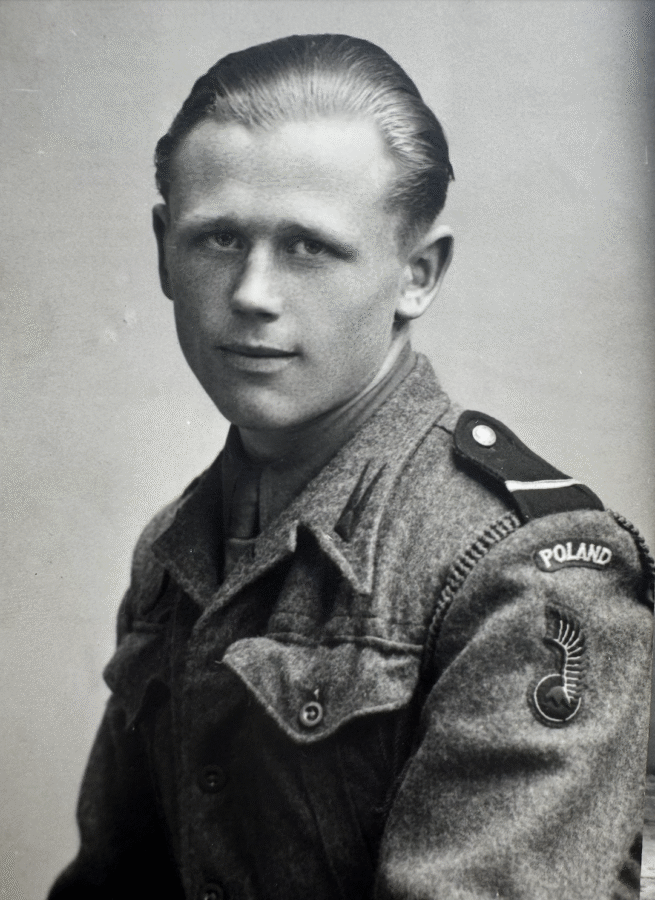

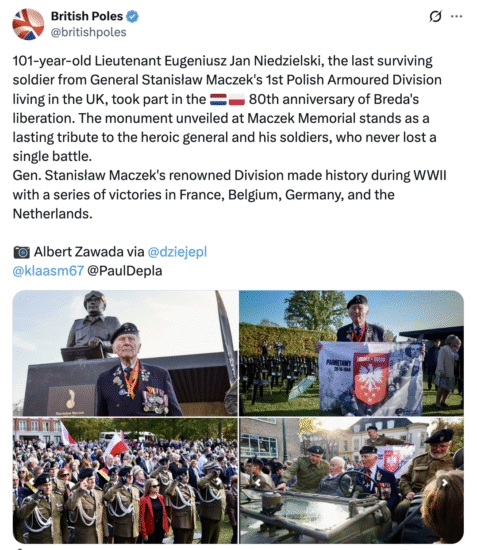

Captain Eugeniusz Niedzielski, nom de guerre “Nead”, is the last surviving soldier of General Stanisław Maczek’s 1st Polish Armoured Division. He has lived in London since the war. On the occasion of his 102nd birthday, we visited him to offer our congratulations. Captain Niedzielski shared with us his memories of the battle trail he followed with his division, as well as his experiences of life in exile in England.

On this occasion, we conducted an interview to share his life wisdom and memories with our readers. Veterans of his age are among the few remaining witnesses of WWII, and every word they speak carries the weight of a historical document.

Maria Byczynski, British Poles: Eugeniusz, you are turning 102 years old. More than 250,000 Poles from the Polish Armed Forces in the West fought against Germany during WW2. You were one of them. Our readers are very eager to hear your memories. Could you please tell us where you were born?

Eugeniusz Niedzielski: From what I remember and what my mother told me, I was born on 1 September 1923 in Dubno, Volhynia—now part of Ukraine. When the Soviets arrived in 1940, my mother took a few essential items, mainly food and warm clothes. No documents proving my birthplace have survived, which is why I still lack Polish citizenship today.

MB: Did you have any siblings?

EN: I had two younger sisters. My father was a soldier, serving in the Legions. He fought in the 1920 Battle of Warsaw, known as the Miracle on the Vistula. The Russians captured him and intended to execute him, but his brother learned where he was held and rescued him. We fled to Berestechko (Beresteczko), where many Poles lived, and he was given land there. After his death, my mother was left alone with three children. I was 14 and helped her with the farm. Sadly, war broke out, and Stalin ordered homes and orchards burned. Deportations of Poles began in September 1939.

MB: When were you sent to Siberia?

EN: On 10 February 1940—my mother, my two sisters aged 9 and 12, and me. They were so young. We had one hour to pack. Under armed guard, we were taken by sled to a station where a long train of about 20 cattle wagons awaited. They loaded us into a wagon with a hole in the floor for sanitation. We endured two weeks of freezing cold—the Russian winter, unlike anything today.

MB: Where did you arrive?

EN: At the last railway station, in a settlement built earlier by deported Ukrainians. We worked felling trees, completely cut off from the world, unaware of the war, without even electricity.

MB: How long were you there?

EN: Until mid-1941. Then the Russians declared us free under the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement of 30 July 1941. They were forming an army. We set off on foot for the station, a walk that took us several days. Then we travelled to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. I tried to enlist, but they wouldn’t take me. There were two officers—a Polish one and a Russian one. The Polish officer, part of a commission enlisting soldiers to the army, enlisted me, but the Russian officer said, “Kid, get lost.”

My mother found me crying, wrote something in Russian, and the next day I returned to a different officer who accepted me. We took a train to Persia, then Palestine. After several months, we boarded a ship through the Suez Canal to Durban, South Africa. I volunteered there and eventually reached a small Scottish village with just four barracks, where I trained as a mechanic. In Scotland we underwent very intensive training. By the time we went to France, we were exceptionally well prepared. After a few months, I was assigned to the 10th Armoured Cavalry Brigade under General Maczek.

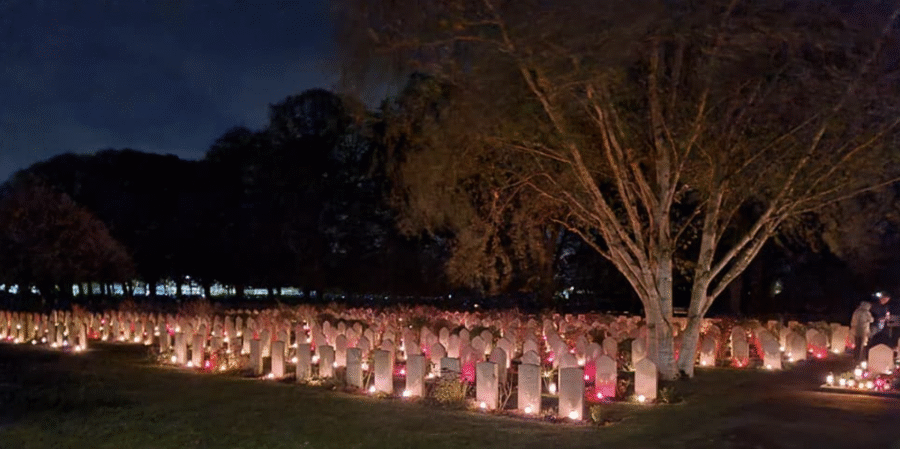

In Scotland we underwent very intensive training. By the time we went to France, we were exceptionally well prepared. In 1944, we were taken to England, then to the front in France. We landed in Caen in June—our forces were the first. Americans and Canadians arrived later. General Maczek told the Polish troops, “We’re not fighting for Poland. We fight for a free world and free Europe, for Poland is betrayed.” I started as a senior rifleman, but in Caen a tank driver fell ill and was hospitalised. With a Scottish driving license for all military vehicles, I took over the tank and drove it through to Germany. We covered the entire route—from Falaise, through Belgium, the Netherlands—to Wilhelmshaven, where the Germans surrendered. I served with the 1st Armoured Division in Germany until March 1947.

MB: Did you return to England?

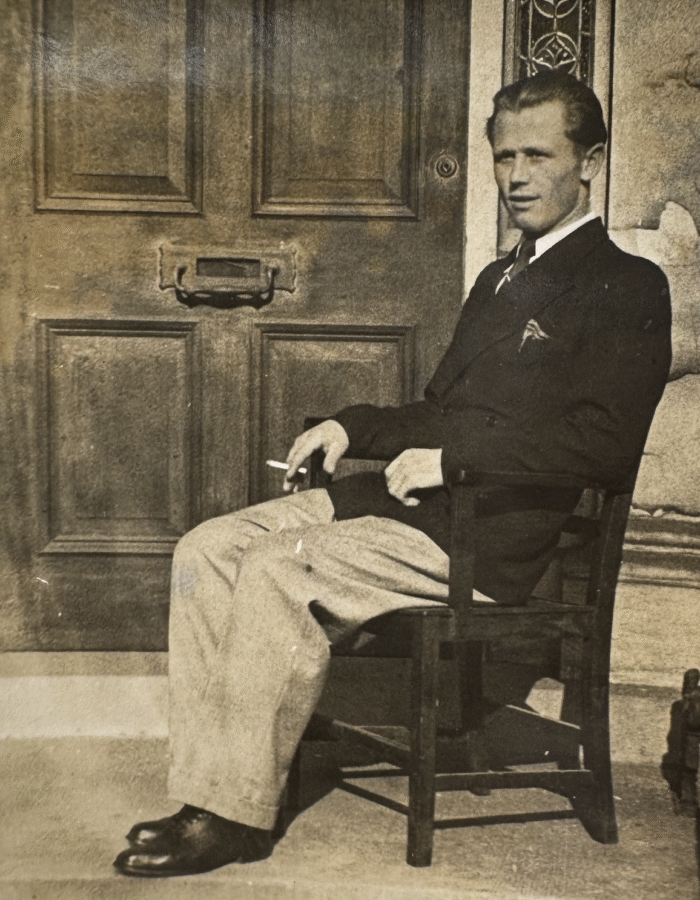

EN: In Breda, we could stay and live for free. In gratitude for liberating the city, we were granted honorary citizenship. Some stayed. Returning to communist Poland was impossible—my mother warned me in letters that nothing good awaited me there. I returned to England. I corresponded with my mother and sisters. Thousands of women also had to leave Russia. My mother, just 33, travelled to Persia, then Mexico, via a ship through Australia and New Zealand. In California, American troops guarded passengers with rifles to prevent escapes from the ship or trains.

MB: How were you received in England?

EN: At that time, the Labour Party, like today, governed England and didn’t want Poles or our army. Churchill eventually persuaded them. Poles resisted working in mines but had no choice. Even General Maczek was denied combatant rights and a military pension by the British government. He worked as a bartender in the Learmonth Hotel until the 1960s to make ends meet. I started in construction. Later, Polish women liberated by our divisions from Germany arrived.

MB: From the Warsaw Uprising? The Oberlangen camp?

EN: Yes, all of them! General Maczek liberated them. I worked in London, near Wembley, living in Ealing. I’d travel from Ealing to dances on Saturday and Sunday evenings—everywhere was lively thanks to Poles. Without us, there’d be no fun. There, I met my wife. We married, had two children, and bought a small house in Kingston, where I’ve lived for 70 years!

MB: What is your current military rank?

EN: Last year in Breda, I was secretly promoted to captain. They took me to a grand palace with a red carpet. The consul attended, along with the Polish Army with an orchestra, several generals, and Defence Attaché Colonel Rafał Nowak, who is now in London.

MB: Congratulations and thank you for these wonderful memories. What are your plans?

EN: I’m reportedly the last living soldier of General Maczek. I’m invited to many ceremonies. I just returned from Scotland and will attend the Market Garden commemoration on 4 September.

MB: Thank you so much for the interview. It’s a great honour to share your memories with our readers, offering a rare chance to connect with living history and the generation that fought for freedom.

Interviewed by: Maria Byczynski

Photos: Private archive of Eugeniusz Niedzielski, British Poles

You can read more about General Stanisław Maczek in our article General Maczek and his Black Devils – the Polish military arm in the West.