Jan Kowalewski was born on 23 October 1892 in Łódź, which was then in the Russian-partitioned area of Poland. He completed his matriculation at the Commercial School of the Łódź Trading Society in 1910. He then travelled to Belgium to study at the Faculty of Technical Chemistry in Liège, and in 1913, he graduated from the University of Liège.

Just before the outbreak of the First World War, he moved to Ukraine and took up a post as a chemical engineer. With the war’s eruption, he was mobilised into the Russian Army and sent to an officer school in Kyiv, ultimately seeing service on the Romanian front.

Following the February Revolution of 1917, Kowalewski joined the Union of Polish Military Organisations and later served in the Polish II Corps, where he was involved in producing soldiers’ newspapers and participated in the Battle of Kaniow. He escaped German captivity and returned to work with the Polish Military Organisation. By the summer of 1918, he had been appointed head of the intelligence section of the 4th Polish Rifle Division under General Lucjan Żeligowski in southern Russia. This marked the beginning of his intelligence career in Poland.

His early life story and military service also served as a motive for one of the main characters of the modern Polish TV series “1920, War and Love”, which is accessible on YouTube with English subtitles.

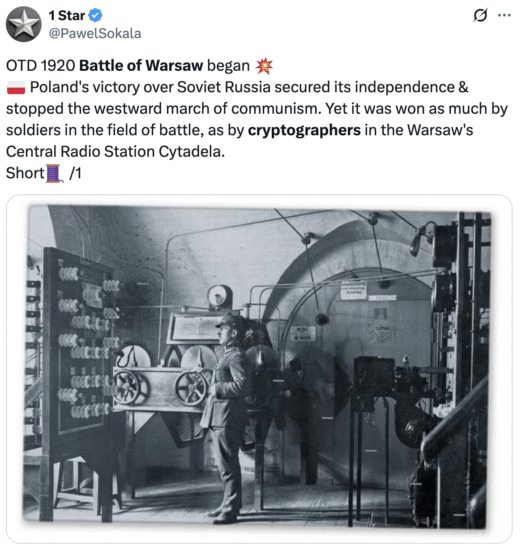

In the early days of Poland’s re-establishment as a state, the Polish General Staff recognised the importance of wireless communications and radio-intelligence. The Russian Army was sending orders in open or very weakly coded text; Polish radio-telegraphers gained experience across all armies of the region. One of the most remarkable exceptions among these recruits was Jan Kowalewski, who in Spring 1919 joined the newly-formed Cypher Section of Division II of the Polish General Staff. His recommendation came from Major Ignacy Matuszewski, who valued Kowalewski’s intimate knowledge of Russian communications structures (now inherited by the Bolsheviks) as well as his command of German, Russian and French.

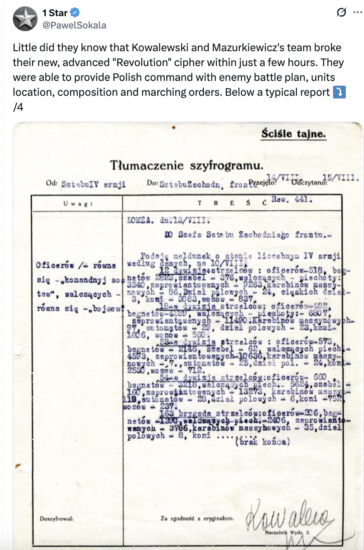

His real break came when he was assigned to sort intercepted Soviet radio-telegraphic dispatches. He noticed that the Russian word for “division” (“divisiya”) contains three occurrences of the letter “i”. Exploiting that pattern, he cracked the inadequate Soviet cypher system. This achievement allowed him and his team to anticipate Soviet troop movements and concentrate on enemy weaknesses. Between August 1919 and February 1920, his Section and the Polish Cypher Bureau decrypted nearly 400 Soviet dispatches despite the Soviets changing their secret codes at least 22 times in that period; Kowalewski personally broke 21 of them.

Between June and the armistice in October 1920, the team cracked 41 codes, 22 of which were his alone. Thanks to these breakthroughs, the Poles had critical intelligence. For example, in early August 1920, when the Red Army was pressing towards the Vistula, the Polish radio-intelligence already had a clear picture of the front. Kowalewski later recalled that although they did not initially know the exact extent of the so-called Mozyr Group, they observed that its communications were stretched and thus vulnerable. On 12 August, he broke another key cypher (“Rewolucja”), and the intercepted messages fed directly into the decision to launch the Polish counter-offensive from the Wieprz.

His contributions were recognised with the Virtuti Militari (5th Class). Higher awards would have risked disclosing the full extent of his intelligence achievements.

After the Polish-Soviet war, Kowalewski served in the region of Central Lithuania, where he commanded a company. He also took part in the Third Silesian Uprising as chief of intelligence for the insurgent units. In 1923, he travelled to Tokyo to instruct Japanese military officers in radio-intelligence methods.

Upon his return, he was promoted to major and assigned further studies at the French War College (École Supérieure de Guerre) from 1925 to 1927. Afterwards, he served as military attaché in Moscow (1929–33), where he conducted intelligence operations on the Soviet Army, while gathering agents and analysing the mood in the USSR. He was promoted to lieutenant-colonel, but in 1933 the arrest of a Polish embassy servant led to his recall from Moscow.

Subsequently, he was posted to Bucharest, continuing his intelligence work in the context of Poland’s southern strategic flank vis-à-vis the USSR. In 1937, he returned to Poland and became chief of staff of the Camp of National Unity (Obóz Zjednoczenia Narodowego), though he resigned less than a year later. He then headed the company “TISSA”, responsible for importing strategic raw materials for Poland’s defence industry. In the run-up to the Second World War, he also became involved in the Baltic–Black Sea canal project.

When war broke out in 1939, Kowalewski helped civilian relief efforts in Warsaw and participated in the evacuation of the Polish government to Romania. Following Poland’s defeat in the September campaign, he led the refugee aid committee in Bucharest until the end of 1939. In early 1940, he moved to France, where he authored two memoranda: one setting out Poland’s only route to reconciliation with the USSR (on condition of recognition of the Riga border) and the other addressed to Germany, urging moderation towards the Polish population, anticipating any future negotiations.

The work of his Cypher Bureau also largely contributed to the final breaking of the Enigma code, which is explained in the video of Epic History TV.

On the fall of France, he relocated to Portugal. From 1941, he headed the “Akcja Kontynentalna” representation in Lisbon under the Polish government-in-exile, supervising intelligence operations across Europe and conducting secret negotiations with Hungary, Romania and Italy (Operation “Trójnóg”) on their possible disengagement from the Axis. He also engaged with the German anti-Hitler opposition. He participated in the rescue of King Carol II of Romania, guiding him into Portugal with the help of Major Zdzisław Żórawski. In 1944, he arrived in the United Kingdom and was appointed head of the Polish Operational Bureau at the Special Forces Headquarters and coordinated the preparation of Polish units for Operation Overlord.

After the war, he remained in exile. He edited the periodical East Europe (from 1950 titled East Europe and Soviet Russia) and collaborated with Radio Free Europe. Between 1958 and 1959, he chaired the Higher Studies Circle in London. He continued his cryptological work; his final achievement was breaking the cypher used by the Polish National Government (the so-called Traugutt cyphers) for correspondence with foreign missions and internal communications.

Jan Kowalewski died on 31 October 1965 in London. Posthumously, he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta. On 17 October 2019, the Polish Senate passed a resolution declaring 2020 the Year of Jan Kowalewski to honour his contributions and the achievements of Polish science and technical thought. On 22 September 2020, President Andrzej Duda promoted him posthumously to the rank of Brigadier-General.

Jan Kowalewski exemplified the interplay of technical brilliance, linguistic skill, and strategic insight. His work in radio-intelligence significantly altered the course of the Polish-Soviet war, and his later diplomatic and intelligence activities spanned continents and conflicts. While his name may not yet be widely known beyond history buffs’ circles, his achievements represent a key chapter in the history of cryptology, intelligence and modern warfare.

Source: Dzieje.pl

Photo: X @MirekSzponar

Tomasz Modrzejewski