By the time a cardboard box of jam doughnuts lands in a modern office kitchen, Fat Thursday can look like a cheerful footnote, a sweet excuse for a midweek treat. But in the Polish imagination, the day has a much longer, louder pedigree, rooted in an ancient rhythm of life where fasting and feasting shaped not only diets, but the social calendar itself.

That is the picture sketched by historian Professor Jarosław Dumanowski in an interview with PAP, in which he reminds readers that Fat Thursday was once just one bright flare amid the whole final stretch of Carnival.

“Fat Thursday used to be part of a week-long frenzy of revelry, sleigh rides and unrestrained feasting,” he told PAP, a description that reframes the tradition as less of a single indulgent day and more of a communal crescendo.

For Dumanowski, the roots run deep. Because fasting reaches back to early Christianity, he argues, so too does the instinct to push back against it beforehand.

The ostatki, the last week of Carnival, appear almost automatically, he says, because forty days of constraints on food and social life created a powerful need to live “on credit” before austerity set in.

In the past, that “credit” was taken seriously. Dumanowski describes celebrations that could run without pause, with feasting so lavish that eighteenth-century observers wrote of it as “one great bout of drunkenness.” Even the geography of celebration was different: rather than people gathering in one place, the party itself could travel.

Perhaps nothing captures that older spirit better than the kulig, commonly translated as a sleigh ride but, as Dumanowski insists, closer in spirit to a moving banquet. In period accounts, it was “a roving feast” that grew as it went, house by house, neighbour by neighbour. People would arrive, “eat through their stores and drink alcohol,” then set off again “in an ever larger group,” leaving “emptied larders” behind.

His phrase for it is unforgettable: “It was socially accepted chaos.” In other words, excess wasn’t merely tolerated; it was expected, performed and shared.

Today, it is the doughnut pączek that has become the edible emblem of Fat Thursday. But Dumanowski’s explanation is not simply that people enjoyed sweet pastries. He points to the severity of historical fasting rules, which not only ban meat, but also “animal fats, butter and eggs.” In that context, deep-fried doughnuts made with rich fats and plenty of eggs were a kind of edible farewell.

“They were the essence of what was about to disappear from the menu,” he tells PAP. By eating them, people were “symbolically saying goodbye to Carnival”, a ritual of transition as much as a treat.

If modern doughnuts are soft, airy and uniform, earlier versions were more varied and sometimes startlingly robust. Dumanowski notes that older pączki could resemble fritters, be fried shallowly, or even baked.

They were “harder, denser,” and he recalls a famous, tongue-in-cheek observation by Jędrzej Kitowicz: “You could give someone a black eye with them.” It is satire, Dumanowski says, but it carries a point. These were not always the pillowy pastries people expect today.

Even the fillings tell a story of changing tastes and techniques. Dumanowski points to a seventeenth-century recipe world where doughnuts might be stuffed with fruits such as elderberry or rose, and later confectioners’ notes that mention almond, cinnamon, coriander, or sugar syrup are a reminder that “traditional” has never meant static.

The end of Carnival had other edible symbols too. Faworki crisp ribbons, often called angel wings, arrived later but quickly gained their own social role. The very word, Dumanowski explains, comes from the French faveur, meaning “ribbon,” reflecting their shape. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, to be invited “for faworki” could mean an entire evening of hospitality, much as certain foods can stand in for whole festivals.

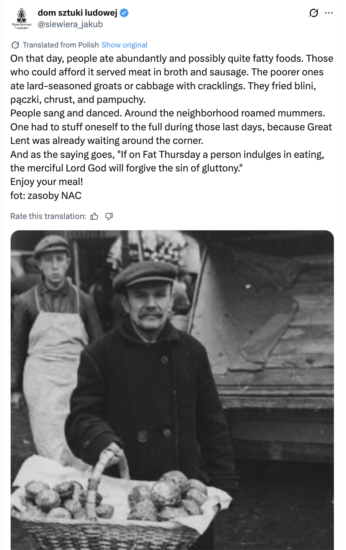

And the celebrations were not confined to the nobility. Dumanowski stresses that peasants also observed the pre-Lenten surge in some cases even more keenly, because the fast “applied to everyone,” and could be “even harsher” for the poor.

Inns became busy, he says, partly because during Lent they might close or restrict sales. The finale came with śledzik, the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday: “the last, very intense party,” sometimes stretching beyond midnight and according to sources, even “several more days.”

So why does a tradition born of communal intensity now appear as a quick office ritual? Dumanowski’s answer is blunt: fasting itself faded as a widespread social practice. Without the shared discipline of Lent, the symbolic power of its prelude weakened too.

“Food became cheap and accessible,” he says, and “it lost its symbolic weight.” In a line that lands with modern precision, he adds: “It’s hard to treat a discount-store doughnut as a feast day.”

Yet he does not suggest the day is meaningless. Something remains: a cultural permission slip. Fat Thursday today is, in his words, “permission for a brief deviation from dieting, from everyday discipline.”

The ritual has shifted from the village and the manor to the individual, from the roar of communal chaos to the quiet satisfaction of one sweet bite, but “paradoxically,” as he notes, it has survived.

And perhaps that survival is its own kind of continuity: even in miniature form, the doughnut still marks a moment when ordinary rules loosen, and people give themselves leave to celebrate if only for as long as it takes to wipe the sugar from their fingers.

Photo: X/@PLinPakistan

Tomasz Modrzejewski