General Władysław Sikorski, the leader of the Polish government-in-exile in the Second World War, tragically lost his life, alongside his daughter and numerous individuals, on 4 July 1943, when the aircraft they were aboard encountered enigmatic circumstances and crashed shortly after departing from Gibraltar.

He was a crucial partner to Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill and contributed troops to numerous pivotal engagements. Notably, during the Battle of Britain, the Polish air force was vital in safeguarding the UK against German aerial assaults.

Władysław Sikorski was born on the 20th of May 1881. In 1898 he began to attend the Teachers’ College in Rzeszów. In 1902, he passed his final exam and enrolled on the Faculty of Civil Engineering at the Lviv Technical University.

Two years later, he interrupted his studies and was enrolled in the Austrian Army for a one-year military service. As a second lieutenant, he gave clandestine lectures on regular army tactics for the activists of the Polish Socialist Party.

In the late 1910s, he co-founded the illegal Union for Armed Struggle and its overt structure – the Rifle Association. After the outburst of the Balkan War and the establishment of the Provisional Commission of Confederated Independence Parties, Sikorski became the Head of its Military Department.

In 1914, in the face of the imminent great war, he was called up into the Austrian army. He joined the rifle units in Miechów. After the collapse of the idea of the anti-Russian uprising in the Congress Kingdom, he became involved in the creation of the Supreme National Committee, in which he took the office of the Head of its Military Department.

He promoted the idea of the expansion of the Legions, in opposition to Józef Piłsudski, who was reluctant to see Polish regiments under Austrian command. After the dissolution of the Legions, Sikorski continued recruitment to the Polish Armed Forces.

Shortly after the “oath crisis” of 1917, the 2nd Brigade of the Legions fought its way to the Russian side of the front in Rarańcza, but Sikorski was arrested. He was sent to the Huszt detention camp, where he was put under trial.

Thanks to the intervention of the Polish MPs in Vienna he was released from internment. In the autumn of 1918, he was staying in where he organised the relief of the city which was under Ukrainian siege at that time.

At the beginning of 1920, Sikorski was appointed brigade general and commander of an operation group. On the 6th of August 1920, Sikorski was given command of the 5th Army which was then created ad hoc. Under his command, the army counter-attacked on the flank of the Soviet forces marching on Warsaw.

He was then promoted to the rank of Division General and appointed Commander of the General Staff of the Polish Army. After President Gabriel Narutowicz was assassinated in December 1922, Sikorski was appointed Prime Minister, taking control of the situation, as the country was under a threat of civil war.

In the years 1924-1925, Sikorski was Minister of Military Affairs. He restructured the army and provided it with modern equipment to make it one of the strongest in Europe at that time.

After a clash with Józef Piłsudski concerning the organisational system of the highest military authorities in 1925, Sikorski resigned from the post of minister. He became the District Commander of the 6th Crops in Lviv.

During the May Coup of 1926, he remained passive – he did not believe that the units faithful to the government would win but did not want to support his opponent. Three years later, he was removed from command and remained at the Minister of Military Affairs’ disposal, with no specific commission.

In September 1939, Sikorski took command of newly formed Polish divisions. After Władysław Raczkiewicz became President, a meeting of Polish political leaders in Paris decided to form the government in which Sikorski was appointed Prime Minister and the Minister for Military Affairs.

A few weeks later, Sikorski was also appointed Commander-in-Chief. As a result of his endeavours, four infantry divisions were formed in France and the Independent Carpathian Rifle Brigade was established in the Middle East. He also started a diplomatic campaign to encourage Polish-American citizens in both Americas to join the army.

Unfortunately, Sikorski’s efforts to mobilise American Poles did not bring the results expected. His talks with the President of the USA about the shape of a post-war Europe ended in a fiasco. Franklin Delano Roosevelt did not agree to take Eastern Prussia from the Germans and give it to Poland.

The Czechs withdrew from negotiations about a potential confederation in post-war Europe. When the Germans announced the discovery of mass graves of Polish officers in Katyń in Spring 1943, Polish-Soviet diplomatic relations were broken, and what followed the issue of the Polish Eastern Borderland was suspended in a political void.

On the 4th of July 1943, a Liberator AL 523 from a special transport division for VIPs, with a Czech pilot Captain Eduard Prchal, set off from the runway at the foot of the legendary rock. A few seconds later, the plane fell into the sea from the height of 300 hundred feet. A rescue action was undertaken immediately, but with no success. Only the pilot was saved, while all the passengers, including Prime Minister Sikorski and his daughter Zofia Leśniowska, were killed.

A British court of inquiry was set up to examine the circumstances which led to the plane crash. The investigators ruled out sabotage, adopting the version of an accident in which jammed elevator controls were to be blamed. Since the documents of the court still remain secret, speculations about the true reasons for the crash continue to reappear. The British, German and Soviet intelligence as well as some Polish political circles hostile to Sikorski have been accused of the assassination of the Polish Prime Minister, however, the true reasons for the tragedy remain of à mystery up until this day.

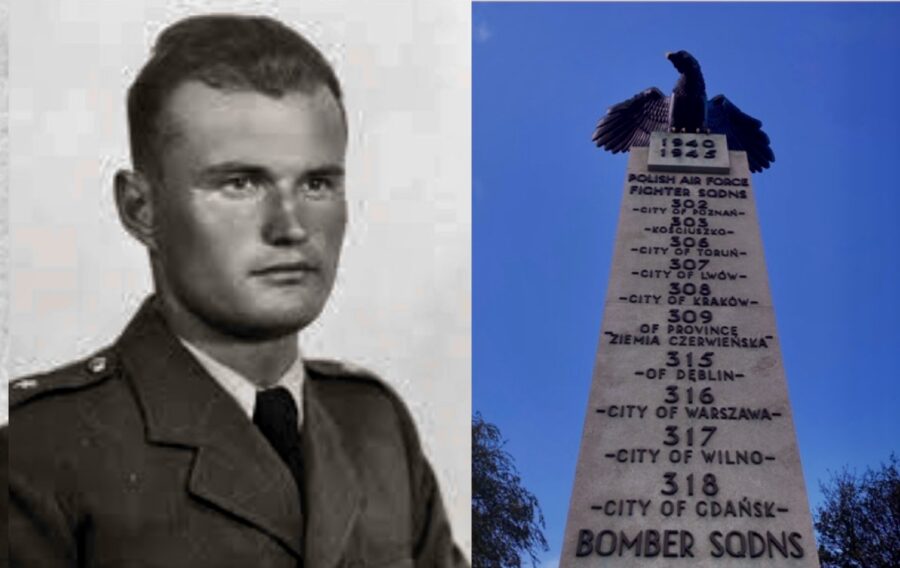

Image: Institute of National Remembrance

Author: Sébastien Meuwissen