On 3 November 1920, in the town of Drohobycz in Galicia, Maciej Aleksy Dawidowski was born into an unusual domestic environment for the era. His parents, Janina and Aleksy, both engineers by profession, mother chemist, father technologist, provided a household where intellectual rigor, socially-minded enterprise and a sense of civic duty were the norm. Those values will shape the future hero of Polish underground during World War 2, known by every Polish child.

When the family relocated to Warsaw in 1929, his father took up post as administrative director at the State Rifle Factory on Wola and promptly introduced progressive welfare measures: a vocational school for workers’ children, adult education, library and sports facilities.

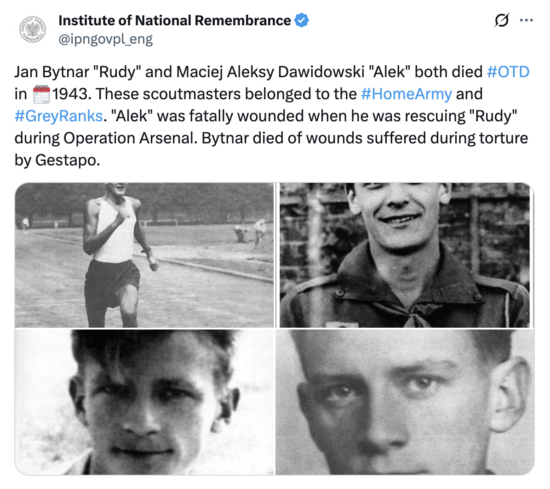

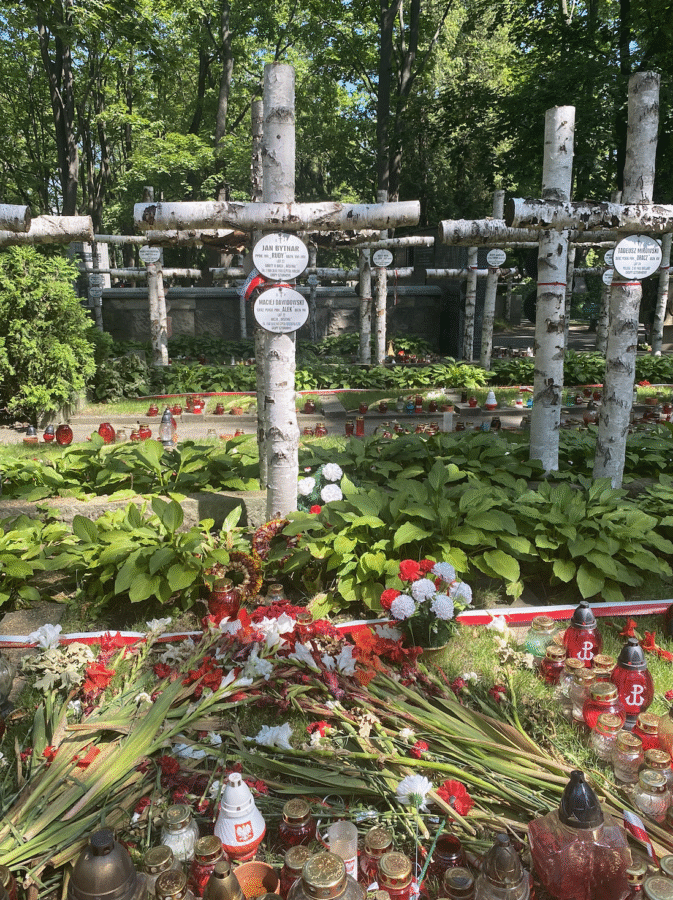

Alek’s schooling at the renowned Stefan Batory Gymnasium further sharpened his physical and intellectual acumen: basketball, swimming, a mathematically-and-scientifically focussed class and a circle of companions Jan Bytnar, Tadeusz Zawadzki et al. who would become legends in Warsaw’s resistance movement.

In 1933 he joined the 23rd Warsaw Scout Troop, dubbed “Pomarańczarnia”. By May 1939 he had finished his matriculation only to face the eruption of war instead of university. As the German occupation descended, the Dawidowski family were directly targeted: his father arrested and executed for refusing to collaborate, his mother later imprisoned in concentration camps.

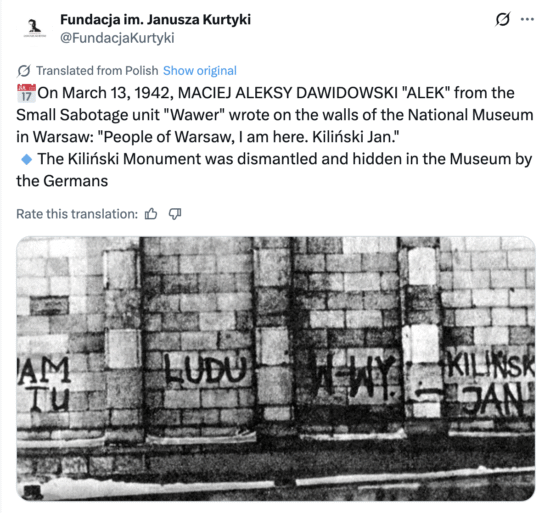

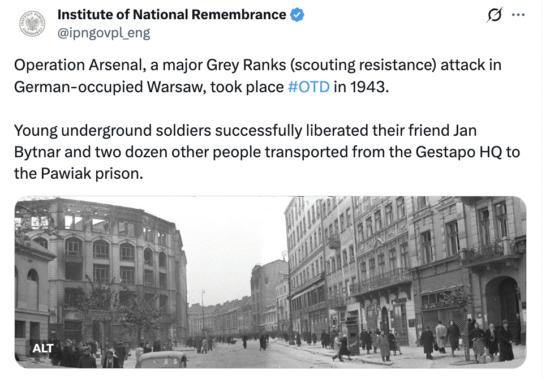

Amid that dark chapter, Alek’s courageous character emerged. He joined the clandestine Grey Ranks (Szare Szeregi) in 1941, operating in the “Wawer” Little Sabotage Unit.

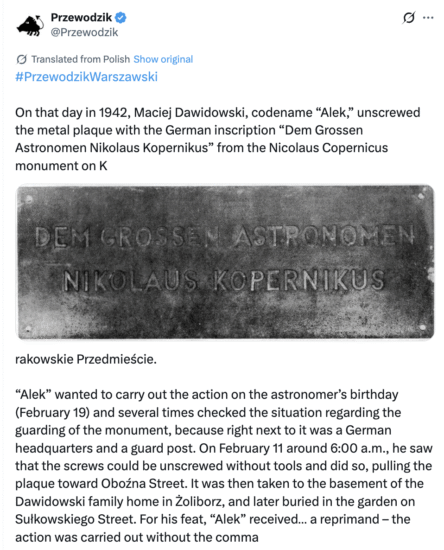

He undertook audacious missions notably on 11 February 1942, in broad daylight and under the nose of occupying forces, he quietly dismantled a German plaque from the Copernicus Monument in Warsaw.

His pluck alone, disguised as a drunken passer-by, his hands unscrewing bolts, a brass slab crashing to the snowy pavement became a psychological blow to German occupation authorities, described by General Bór-Komorowski as “one of the best pranks” in the psychological war.

But the daring exterior concealed deeper currents of introspection. In his private notes, Alek wrestled with moral dilemmas: the right to kill, the cost of resistance, the weight of conscience.

Having lost his father to the occupiers, his mother in camps, he valued humanity even in the enemy, as his comrade Jan Rossman later said: “In the mortal enemy, who had killed his father, he sought to respect a human being.”

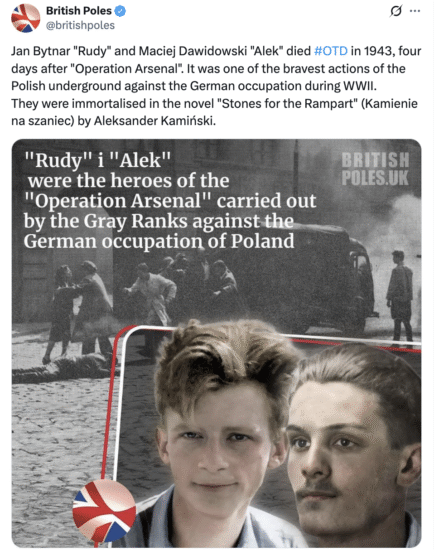

By early 1943, he was deputy commander of a sabotage and diversion platoon under Jan Bytnar “Rudy”. His final mission came in March: during the rescue of “Rudy” in the “Arsenal” operation, he was gravely wounded and died on 30 March 1943, aged just 22.

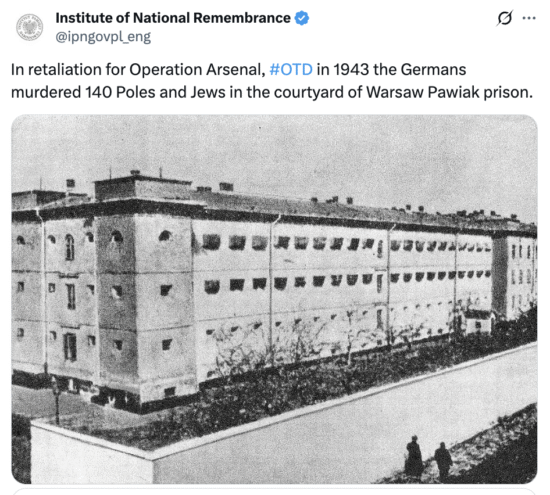

“During the retreat from the Arsenal, Maciej Aleksy Dawidowski, known as “Alek”, was also mortally wounded. In retaliation for this operation, the Germans executed 140 prisoners from Pawiak prison,” Curator of the Pawiak Prison Museum, Robert Hasselbusch, told in an interview for the Polish Press Agency.

On 3 May the same year, in recognition of his actions, he was posthumously awarded Poland’s highest military honour, the Cross of the Order of Virtuti Militari, and promoted to sergeant-cadet, the first Scout of the Grey Ranks to receive it.

Today, his story stands not only as a testament to youthful bravery in the face of tyranny, but also as an exemplar of ethical reflection amid armed struggle: a young man who moved beyond the slogans to ask whether resistance must compromise humanity, and who strove to act in a way that honoured both honour and conscience.

Photo: X/@KolorHistorii, British Poles

Tomasz Modrzejewski