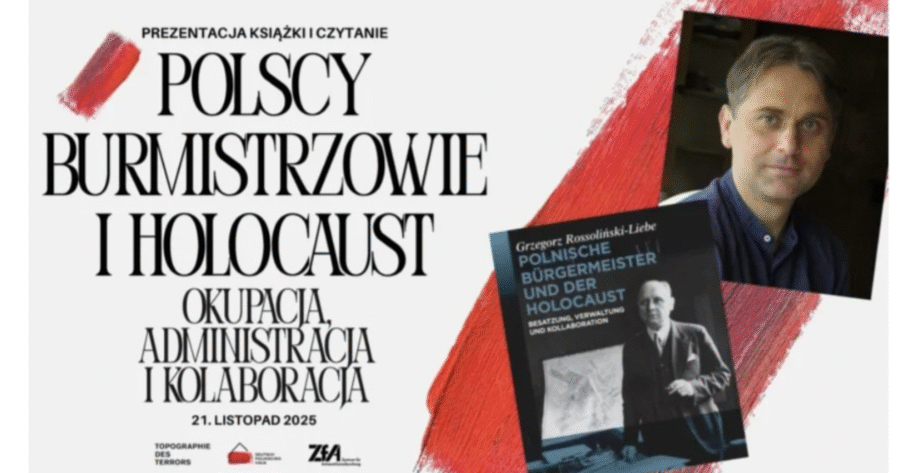

A controversial event has exposed deep tensions lurking beneath Polish-German relations. The planned meeting, “Polish Mayors and the Holocaust: Occupation, Administration and Collaboration”, scheduled for 25 November at Berlin’s “Topography of Terror” institution, has been unexpectedly postponed due to strong reactions from Poland.

Originally co-organised by the Polish-German House and hosted by the memorial centre documenting German Nazi crimes, the event was to feature Polish-German historian Dr Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe.

His 2024 book describes the role of Polish municipal officials in the Nazi-controlled General Government during the Second World War. According to the event announcement, these mayors “together … shaped local policy and were significantly involved in the persecution and murder of Polish and European Jews.” But soon after, the event was called off “without explanation,” Rossoliński-Liebe told press.

Behind the scenes, the cancellation is said to stem from a diplomatic intervention. Poland’s ambassador in Berlin reportedly phoned Uwe Neumärker, the director of the host foundation, requesting the meeting be dropped, seemingly amid fears the topic could overshadow upcoming bilateral discussions and plans for a monument to Polish victims of the war.

The episode has sparked fierce reactions in Poland. One voice in the European Parliament, MEP Arkadiusz Mularczyk, denounced the meeting as “rewriting history… blurring the line between perpetrator and victim.”

The historian, for his part, warned that the incident undermines academic freedom and raised concerns that future German institutions might pre-emptively bow to diplomatic pressure.

At its heart, the affair exposes an uneasy truth: the legacy of the war remains a political minefield. Research into collaboration during the German occupation continues to be sensitive in Poland, where dominant narratives emphasise heroic resistance rather than administrative complicity.

Rossoliński-Liebe says his own efforts in Poland have faced institutional resistance, but being blocked in Germany “comes as a shock.”

Meanwhile, a peer review of the book was published by the Polish Institute of National Remembrance.

“Crucially, the author creates a picture of the German occupation in which the Germans, as occupiers, have been relegated to the background. This is evidenced by the lack of context and description of their actions, starting from September 1939, through the issue of the displacement of Poles and Jews from the territories incorporated into the Reich, the matter of terror against Jews, including the establishment of Judenräte and the creation of ghettos, as well as the role of the administration and German security forces in the liquidation of ghettos and the deportation of Jews.

Furthermore, Polish mayors were entangled in this world, artificially created by the author—alleged realities of the occupation with a limited role for the Germans—who, in Rossoliński-Liebe’s narrative, falsely assume the role of equal partners to the Germans, also participating in the Holocaust. As the author writes: „the participation of Polish mayors in the Holocaust was a significant contribution to this enormous crime.”

In summary, Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe’s book, while creating a semblance of academic rigour, fails to observe the principles of historical methodology. One gets the impression that its goal is to convince the academic world that local municipal officials in the General Government (GG), especially Polish mayors, were co-responsible for the Holocaust (starting as early as 1939), while the role of the Germans—in the author’s view—was marginal,” writes an IPN historian and autor of the review Damian Sitkiewicz.

The full text of the review in Polish is accessible for free in this link:

https://czasopisma.ipn.gov.pl/index.php/pjs/article/view/2761/2730?s=08

Photo: Dom Polsko-Niemiecki

Tomasz Modrzejewski