Few figures in twentieth-century Polish political life embodied contradiction as vividly as Stanisław Cat-Mackiewicz. Monarchist in instinct yet modern in polemical style, conservative in outlook yet rebellious in temperament, he was a man who seemed destined to quarrel with governments, with émigré leaders, with censors, and ultimately with history itself.

Born in the waning years of the partitions, Mackiewicz came of age in a Poland that had just regained its independence. He became one of the most distinctive voices of the conservative right, associated with the Vilnius daily Słowo.

His pen was sharp, ironic, and frequently merciless. Unlike many publicists of his generation, he combined historical imagination with political immediacy. He wrote about kings and cabinets, about diplomacy and destiny, always with the conviction that Poland’s tragedy lay not only in foreign aggression but in domestic miscalculation.

“In international politics, there exist laws that operate with the same precision as, for example, the law of supply and demand functions in economic relations. One such law in Polish politics is the dependence of Poland’s strength on the relationship between Germany and Russia. Poland loses whenever cooperation and solidarity prevail between Germany and Russia. Poland’s position immediately grows stronger when antagonism arises between Germany and Russia,” wrote Stanisław Cat-Mackiewicz.

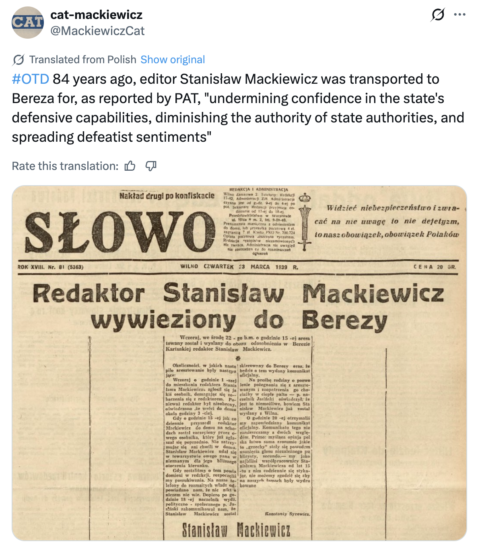

Shortly before the start of the Second World War, Stanisław Cat-Mackiewicz was arrested (as the only Polish journalist) and sent to the infamous Bereza Kartuska camp in response to his articles critical of the insufficient development of the Polish armed forces.

The Second World War and its aftermath deepened his sense of catastrophe. For Mackiewicz, the collapse of the Second Republic was not merely the result of overwhelming force but of flawed judgment at the highest levels.

Mackiewicz was also a staunch critic of Polish foreign policy, which, in his view, led to war and was directed against Polish national interests.

“As the war progressed, it became clear to me that the English had deliberately and provocatively pushed Hitler towards Poland, to divert his first deadly blow away from the West and, above all, to bring about a Russo-German war. The disparity between the reckoning of English blood and our own grew ever more evident, as did the shrugging of shoulders at our national interests,” he wrote.

In exile, particularly in London, he remained an uncompromising critic not only of pre-war policy but also of the émigré establishment.

He was a critic of the newly formed Sikorski government.

“Dunkirk – that is the symbol of true, rational, active patriotism. At a certain moment, not too late, the English recognised that their homeland might be in danger. They then withdrew their troops from the Continent. On 17 June, France asked for an armistice without uttering a single word about Poland, showing no concern for our fate and leaving us to our own devices. And yet our troops continued to fight at the front instead of making for the ships and embarking for England.

I do not enter into a critique of military operations. Had General Sikorski declared that our forces were unable to disengage from the enemy, I would not object. But General Sikorski explained that our troops fought on because national honour did not permit them to abandon their allies. Yet our soldier was needed by Poland in England, not in France. Our soldier is a soldier that is to say, a servant of Poland’s political interests; his honour lies in serving those interests, not in displaying courage in someone else’s cause,” Mackiewicz wrote.

This made him intellectually formidable and politically isolated. He admired strength and clarity; what he saw instead were factional disputes and what he considered political illusion.

“Warsaw was destroyed more thoroughly than Berlin; Poland’s defeat in this war—fought by Poles in the camp of the victors—was greater than Germany’s defeat. The Soviets were intent on the destruction of Warsaw, and it so conveniently happened for them that they did not need to use Soviet guns or shells to accomplish it. After all, there was Polish patriotism! It is great and magnificent. But it possesses the quality of irrational dynamite. It is enough to apply the match of provocation for it to explode.

The Warsaw Uprising surpasses all records of endurance. For many hundreds of years, so long as the Polish nation exists, every Pole will acknowledge that the Warsaw Uprising was a suicidal frenzy, and will feel for it a filial tenderness and love. He will be proud of it…” Mackiewicz wrote after the end of the Warsaw Uprising and German destruction of the Polish capital.

His brief tenure as Prime Minister (8 June 1954 to 21 June 1955) of the Polish government-in-exile was both a culmination and a paradox. It elevated the outsider to the centre, yet gave him almost no real authority.

Mackiewicz approached the role with seriousness, abandoning literary work to focus on state affairs, even though the “state” existed only in diplomatic form. He believed ideas mattered, even when institutions were hollow.

He summed up his year in office in his characteristic style: “My present occupation, purely theatrical of course, has something of a commedia dell’arte about it.”

His role as Prime Minister was mostly ineffective in most of the objectives, which included providing for the Wawel Treasury that was kept in Canada or addressing the so-called Berg controversy that revealed strong ties between the US intelligence and the Polish government in exile

His decision to return to communist Poland in 1956 remains the most controversial act of his life. To some, it was capitulation; to others, a desperate attempt to act within reality rather than shadow. Mackiewicz justified it in geopolitical terms: the West would not liberate Poland, and political fantasy endangered the nation.

At that point, his already bad relations with his brother, an amazing writer – Józef Mackiewicz – ceased to exist.

Yet the return placed him in a morally ambiguous position. He enjoyed privileges, published books, and re-entered public life only to encounter censorship, surveillance, and renewed isolation.

But he also resisted the communist censorship for which he was briefly imprisoned as one of the initiators of the famous Letter of the 34

In the end, he belonged nowhere entirely. The émigrés regarded him as a defector; the communist authorities treated him as a useful but unreliable relic. His letters from the early 1960s reveal a man painfully aware of having misjudged both sides. There is something profoundly tragic in his self-description as a “spectre” too independent for conformity, too restless for compromise.

Mackiewicz’s legacy resists simplification. He was neither hero nor villain in any conventional sense. Rather, he was a political writer of rare courage who refused intellectual comfort.

His writings remain among the classics of Polish political history until today.

Photo: X/IPN

Tomasz Modrzejewski