The Warsaw Uprising, one of the most dramatic and tragic episodes of the Second World War, formally came to an end on 2 October 1944. This insurrection, launched as part of the wider campaign known as Operation Tempest (Akcja „Burza”), was an attempt by the Polish underground state to liberate the capital from German occupation before the arrival of Soviet forces. Despite promises of respecting the POW rights and cultural heritage of Warsaw, the Germans persecuted and murdered both civilians and insurgents and later demolished the entire city, displacing more than 500,000 inhabitants.

The uprising began on 1 August 1944 at five o’clock in the afternoon, the so-called “W-Hour”, when units of the Home Army (Armia Krajowa), supported by reserves from the Central Command, launched attacks across Warsaw. Almost immediately, ordinary civilians threw themselves into the struggle. They built barricades, dug trenches, set up anti-tank obstacles and supported the fighters with food, shelter and medical aid. Alongside the Home Army, units of the National Armed Forces (Narodowe Siły Zbrojne) and the People’s Army (Armia Ludowa) also took part.

Yet the insurgents faced desperate conditions. Although about 30,000 fighters were mobilised, barely one in ten had a weapon. Against them stood a German garrison of roughly 20,000, equipped not only with small arms but with armoured divisions, artillery and aircraft. Hopes of meaningful Allied assistance were soon dashed: supply drops from the air were irregular and insufficient, while the Soviet forces, stationed across the Vistula, offered little help.

Around 3,500 soldiers who served in the Tadeusz Kościuszko Division under the Soviet command took part in the fighting, with most of those who tried to help the Uprising dying in the fighting or during the Vistula River crossing.

After sixty-three days of unrelenting combat, starvation and bombardment, the leadership of the Home Army opened negotiations with the Germans. Talks were held at the headquarters of General Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski in Ożarów Mazowiecki, and on the night of 2–3 October, the act of capitulation was signed.

According to its provisions, insurgents were to be treated as legitimate POWs rather than partisans, the civilian population was to be spared collective punishment, and residents would be allowed to take personal belongings as they were evacuated from the city. The Germans also pledged to safeguard public and private property, particularly Warsaw’s historical monuments. Still, in practice, this promise was soon broken as the occupation forces completely demolished the city building after building.

General Komorowski, recalling the event, wrote:

„For the second time in this war, Warsaw was forced to yield to the enemy’s superiority. At both the beginning and the end of the war, the capital of Poland fought alone. Yet the conditions of the struggle in 1939 were entirely different from those in 1944. Five years earlier, Germany stood at the height of its power, and the weakness of the Allies made it impossible to provide Warsaw with any assistance. The fall of the Polish capital was the first in a series of German victories. In 1944, the situation was reversed. Germany was already in decline, and we all had the bitter conviction that the fall of Warsaw would probably be the last German victory over the Allies.”

„In the initial stage, the Germans certainly adhered to the terms of the agreement. After the Uprising, there were no repetitions of the terrible massacres that had occurred during its course. There was no attempt to hunt down Jews or other ‘undesirable elements’, and, generally speaking, those evacuated to transit camps were neither beaten, starved, nor otherwise maltreated. Many thousands of people found ways to slip through the net, and many others were released at once. The majority of Home Army prisoners were, in accordance with the agreement, sent to regular prisoner-of-war camps under Wehrmacht supervision. (…) Women taken into captivity were, as stipulated, directed to special camps (…) or simply released. Yet as time went on, and the initial mass dwindled, the less pleasant aspects of the Nazi machine began to show. When the final calculations were made, it turned out that well over 100,000 inhabitants of Warsaw had been sent to forced labour in the Reich, in violation of the agreement on the cessation of hostilities in Warsaw, and tens of thousands more were placed in SS concentration camps, including Ravensbrück, Auschwitz and Mauthausen,” wrote Prof. Norman Davies in a comment to how the German forces obeyed to the guarantees given to the AK during capitulation talks.

On 6 October 1944, the first transport of prisoners from the Uprising left Ożarów and, after two days, arrived at Stalag 344 Lamsdorf (Łambinowice) in Upper Silesia, which was the oldest and largest prisoner-of-war camp in the Third Reich.

On 6 and 7 October 1944, a total of 5,789 officers, non-commissioned officers and privates reached the camp at Lamsdorf, among them a group of 600 underage fighters of the Uprising, boys between 12 and 18 years of age. The prisoners remained there until 18 October 1944, after which they were dispersed to various other POW camps, including Woldenberg, Gross-Born, Murnau, Mühlberg, Sandbostel, as well as the Sonderbarakenlager Oflag XI B/Z in Bergen.

The price of the uprising was catastrophic. On the insurgents’ side, around 16,000 were lost, including 10,000 killed and roughly 6,000 missing. Another 15,000 were taken prisoner, among them almost 900 officers and some 2,000 women. The heaviest losses were borne by civilians, with between 150,000 and 200,000 killed, often in mass executions such as those in the Wola district. German casualties are more difficult to establish, with estimates showing around 2,000 dead.

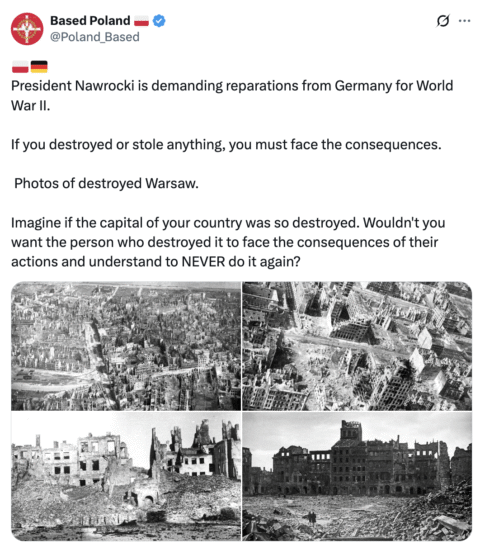

Warsaw itself was left in ruins. During the fighting, about a quarter of the city’s left-bank buildings were destroyed. After the surrender, the Germans embarked on a systematic campaign of demolition, reducing a further thirty per cent of the capital to rubble.

Taken together with the devastation of the 1939 siege and the annihilation of the Jewish Ghetto, the destruction of the left bank reached an almost unimaginable eighty-four per cent. Including the district of Praga on the right bank, the overall damage across Warsaw stood at about sixty-five per cent.

The Warsaw Uprising thus ended not in liberation but in ruin and tragedy. What was intended as a bold strike for freedom became instead a grim chapter in the history of both the city and the nation, remembered today as a symbol of courage, sacrifice and the desperate struggle for independence.

Source: Dzieje.pl, Historykon

Photo: IPPN

Tomasz Modrzejewski