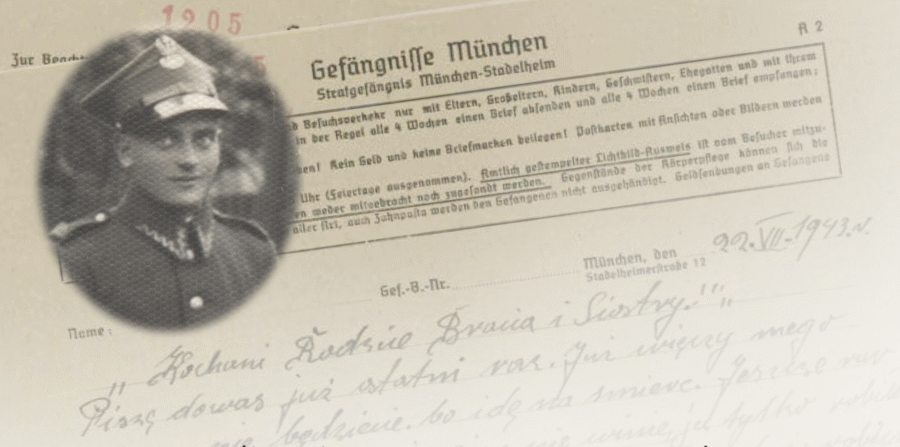

Pilecki began preparations for his mission in the late summer of 1940. While staying at a safehouse, he found identity papers belonging to a man named Tomasz Serafinski, who was erroneously presumed killed in September of 1939. Because the Nazis asked for the names and addresses of inmates and their relatives as a method to keep the population under control, Pilecki wisely decided not to give his real name or those of his immediate family. Pilecki placed his photograph on Serafinski’s papers and memorized his details. His plan was to be arrested and booked under the Serafinski alias.

In the early morning hours of September 19, Nazis did a roundup in Warsaw and arrested as many as 2,000 people. According to Adam Cyra and Wieslaw Wysocki’s 1997 biography Rotmistrz Witold Pilecki, Pilecki was in the apartment of Eleonora Ostrowska the morning of the roundup. A caretaker and member of the resistance came in and made several suggestions to Pilecki for how to avoid being caught. According to Ostrowska, „Witold rejected those opportunities and didn’t even try to hide in my flat.” When a German soldier knocked on the door and asked who lived there, Pilecki walked out. As he was saying goodbye to Ostrowska, he quietly whispered to her, „Report that I have fulfilled the order.”

He called his network the Union of Military Organization, known by its Polish acronym ZOW, and would be part of the Home Army, the Polish resistance. The secrecy of the ZOW’s existence was paramount. To ensure its continuity in the event of discovery by Nazi guards or informants, Pilecki created a highly compartmentalized system of five-man cells. The leader of each cell would be people of utmost confidence, committed to the Polish resistance and able to withstand possible interrogation or investigation by the German guards. Each cell leader swore an oath to Pilecki himself and only knew of the four men under his command, but not of the existence of any other cells. By doing so, Pilecki effectively minimized the risk of exposure to the entire network.

Pawlowicz estimates that Pilecki’s network included some 500 inmates at Auschwitz by March of 1942, but notes this number may have doubled by the time of Pilecki’s escape the following year. In time, Pilecki was able to place informants and allies in key positions throughout the camp. In time, these would prove crucial for Pilecki and other ZOW members.

Life inside Auschwitz tested every inmate. How each of them reacted was entirely subjective. Pilecki wrote, „Camp was a proving ground of character.”

„Some — slithered into a moral swamp.””Others — chiseled themselves a character of finest crystal.”

Pilecki eventually made his way back to Warsaw and reported to the Home Army’s headquarters on August 25, 1943 hoping to find a receptive audience for the ZOW’s idea of taking control of Auschwitz from the inside. Unfortunately for him, his former commanding officer, who had known the purpose of his Auschwitz mission, had been arrested two months earlier and the new leadership was not receptive to his proposal. According to Cyra and Wysocki’s biography of Pilecki, he felt „bitter and disappointed.”

Pilecki’s use of the Tomasz Serafinski alias had unintended consequences for the real Serafinski. The Gestapo arrested Serafinski on Christmas Day of 1943 on charges of escaping from Auschwitz. He was held in a local prison in Bochnia for three days before being handed over to the Gestapo in Krakow. After undergoing what Cyra and Wisocki describe as a „brutal investigation” in which he consistently rejected the accusations against him, Serafinski was released on January 14, 1944. According to Jacek Pawlowicz, Pilecki and Serafinski later became friends, adding „That friendship is alive to this day, because Andrzej Pilecki visits their family and is very welcome there.”

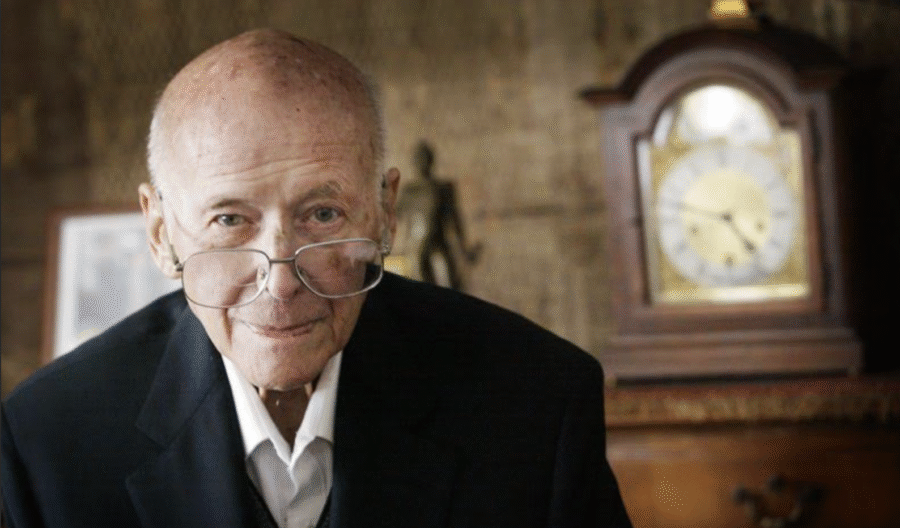

Andrzej Pilecki was 13 or 14 the last time he saw his father in the spring of 1947. At the time, he was living with his mother, sister and two cousins in the town of Ostrow Mazowiecka. At the time, his father was on a mission to convince anti-communist youth resistance living in hiding in the Red Forest by Bialystok to demobilize. „He was to pull out the youth who was in the forest, to let them know that there won’t be a Third World War, so why should they stay in the forest?” Pilecki says of his father’s assignment. „It was a difficult mission. Why? Because he could have been found out and killed on the spot or exiled to Siberia. And he couldn’t reveal himself as an officer for that reason, and the youth would only listen to officers.”

Today, there is a tombstone with what had been an empty grave for Pilecki in this cemetery. Pilecki’s widow Maria, who died in 2002, is now buried there. Flowers, candles and a small Polish flag with the anchor symbolizing the Polish resistance now decorate the gravesite. On the site of the meadow, a brick monument has been built, with small bronze plaques bearing the names of each of the people believed to be buried there, including Pilecki’s. Flowers, candles, and Polish flags decorate the site.