On a cold Christmas Eve in 1798, a child was born whose words would one day become the heartbeat of a nation without borders. Adam Mickiewicz, hailed as Poland’s greatest Romantic, lived a life that was equal parts poetry and upheaval, a journey that carried him from the landscapes of Lithuania, through the salons of Paris, to the distant shores of the Ottoman Empire.

Mickiewicz’s youth was spent close to nature and folklore, among the forests and lakes of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Those surroundings later seeped into his verse the whispering birches, the noble manors, the haunting folk beliefs of the borderlands.

But his talent outgrew provincial life. In Vilnius, where he studied, he joined a secret circle of young intellectuals who believed that books could kindle freedom. It was a dream powerful enough to worry the Russian authorities.

He co-founded the secret patriotic student society known as the Towarzystwo Filomatów (Philomaths), which became famous for its literary and political discussions. His debut poem, Zima miejska (“Winter in the Town”), was published in 1818. A year later, after completing his studies, he moved to Kaunas, where he worked as a school teacher.

“The Philomaths were the most important group within the generation that carried out the Enlightenment-to-Romantic transition in Poland. It was among them that the earliest young authors emerged, those who paved the way for Romanticism,” said Professor Bogusław Dopart, a literary scholar at the Jagiellonian University.

Between 1822 and 1823, the first two volumes of his poems were published, including Ballady i romanse (Ballads and Romances), Grażyna, as well as the second and fourth parts of Dziady (Forefathers’ Eve). In 1823, Mickiewicz was arrested by the tsarist authorities for his membership in the Philomaths; for half a year, he was imprisoned in a Basilian monastery in Vilnius. In 1824, he was sentenced to exile deep within Russia.

His arrest in 1823 marked the beginning of his forced travels around Europe. Exile did not quieten him; instead, it expanded his imagination. In Crimea, he discovered landscapes and cultures unlike any he had known and out of that astonished gaze emerged the Crimean Sonnets, a testament to longing and the poetry of distance.

Mickiewicz’s encounters in Russia with leading thinkers, including the great poet Pushkin, showed that art could serve as a bridge between cultures. Yet he remained, at heart, a pilgrim of the lost homeland.

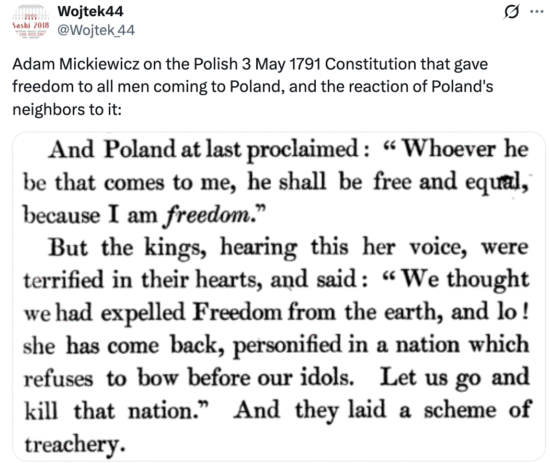

When he finally reached Western Europe, he became more than a poet; he became the spiritual envoy of a nation erased from maps. In Paris, he wrote Pan Tadeusz, the national epic in which he resurrected the world of his childhood, as if words might preserve what history had destroyed.

He hoped, always, for Poland’s rebirth not as nostalgia, but as a living purpose. His later years were marked by activism, teaching, and a restless desire to contribute to Europe’s turbulent politics. Even as illness and fatigue overcame him in distant Istanbul in 1855, he remained in the service of that mission.

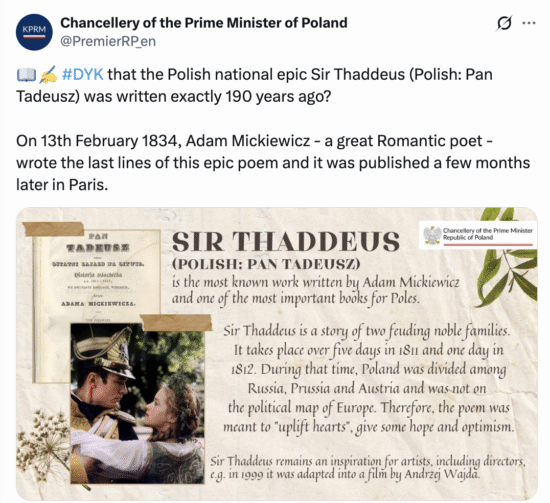

Mickiewicz’s most important work is indeed Pan Tadeusz, or the Last Foray in Lithuania, his epic poem published in two volumes in 1834 in Paris by Aleksander Jełowicki.

This national epic (with elements of the noble tale) was written in Paris between 1833 and 1834. It consists of twelve books in verse, composed in Polish thirteen-syllable alexandrines. The narrative covers five days in the year 1811 and one day in 1812, showing Poland’s history during the Napoleonic wars.

The epic has a permanent place on the Polish school reading list. In 2012, it was read publicly as part of a national campaign promoting the knowledge of Polish literature entitled The National Reading of Pan Tadeusz.

Mickiewicz died on 26 November 1855 in Istanbul.

Adam Mickiewicz lived only 56 years, but each of them was spent in devotion to poetry and to Poland ideas that for him were inseparable. He wrote in exile, but his heart never left the fields, forests and manor houses of the East. His voice continues to resonate wherever people believe that culture and memory can outlast oppression.

More than a century and a half after his death, Adam Mickiewicz still refuses to surrender all his secrets. Officially, cholera carried him off in Istanbul in 1855, yet from the very beginning, many doubted this tidy explanation. The greatest poet of the Polish nation died while preparing a unit to fight against Russia; the timing, his allies and enemies, and the political stakes make coincidence hard to swallow.

Mickiewicz arrived in Ottoman-controlled Constantinople as a man on a mission. Europe was ablaze with the Crimean War, and Poles placed their hope in the conflict as a chance to strike at the Russian Empire and reclaim independence. The poet-turned-organiser set out to unite quarrelling émigré factions: one camp insisted on Polish Catholic troops only, while others, led by Sadyk Pasha, a Polish exile who became a Turkish commander, wanted a multinational legion of Balkan soldiers under Ottoman command. Mickiewicz was the only figure respected enough to calm egos and unite visions. It was a task full of danger.

And then he died suddenly.

Speculation flourished immediately. Russian agents had every reason to sabotage a man determined to raise arms against their empire. To those who suspected poison, the confusion around his illness looked like a cover-up, not a tragedy of disease.

His body, carefully embalmed and transported via a French steamer, was laid to rest in Paris dressed in a fur coat, his heart left in his chest, a death mask preserving his final expression. Not until decades later were his remains returned to Poland, a symbolic homecoming for a poet who died pursuing freedom.

The question persists: did Adam Mickiewicz fall victim to a deadly illness or to the politics he could never escape? His mysterious end has become part of the legend: a Romantic bard whose life and perhaps death were shaped by the struggle for his homeland.

He was a Romantic bard, a rebel in verse, and the wandering conscience of a nation, a poet who carried his homeland within him and presented it to the world through the power of his words.

His probably most poetic depiction of Polishness remains a tribute to all future generations of Poles:

“Our nation is like lava:

Cold, hard, foul and dry upon the crust;

Yet centuries can’t chill the fire inside.

Let us spit on that shell and descend to the depths.”

Photo: X/@Alicja322

Tomasz Modrzejewski