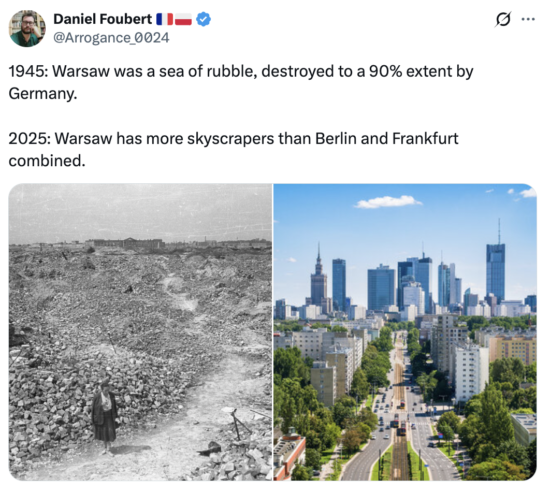

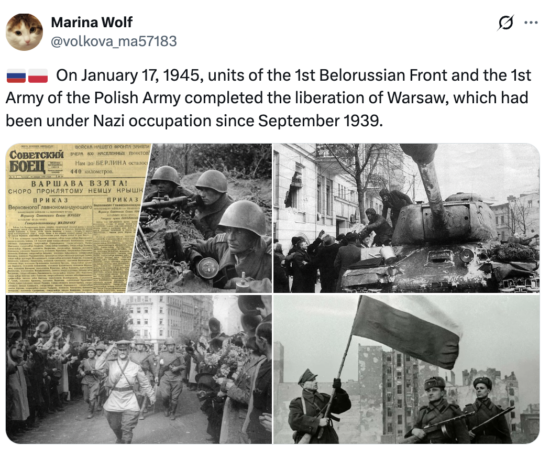

When Soviet and Polish units crossed into the ruins of Warsaw on 17 January 1945, there was no cheering crowd to greet them. What stood before the soldiers was not the Polish capital but its ruins and silence broken only by the crunch of boots on frozen rubble. It was the aftermath of the final battle of the Polish underground Home Army with the Nazi German occupation that failed to see Allied relief.

“For us, it wasn’t a return to life,” says historian Anna Kowalska. “It was a confrontation with absence, with the knowledge that a city had been deliberately murdered.”

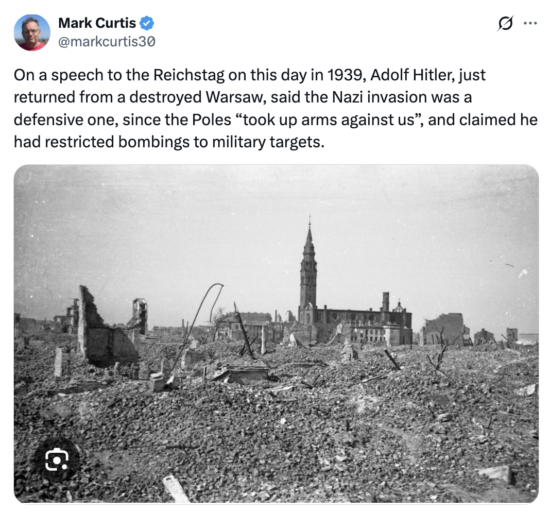

Official announcements spoke of victory and salvation. Newspapers celebrated artillery salutes fired hundreds of kilometres away, while political leaders praised the new Polish-Soviet “brotherhood” forged in battle. Yet on the ground, Warsaw told a different story. The left bank resembled a cemetery more than a city, and even the areas spared destruction bore the marks of terror.

Within weeks, security services had established detention centres in residential buildings. Former resistance fighters disappeared into basements converted into interrogation rooms.

“The war hadn’t ended for us,” recalls a survivor of the underground. “It had simply changed uniforms.”

Across the river, German forces had completed their grim task. Entire districts were stripped bare before being blown apart. Libraries burned, palaces collapsed, and centuries of cultural memory vanished in smoke. One forced labourer later wrote that watching the demolitions felt like “attending an execution where the victim was a city”.

The military operation itself was swift. German commanders withdrew rather than fight over ruins that held no strategic value. By the afternoon of 17 January, the last resistance had been cleared. Mines left behind claimed dozens of lives as an invisible final weapon.

Two days later, a military parade marched through Aleje Jerozolimskie. Political leaders stood on a platform, while soldiers passed between ruins.

At that time, it is estimated that around 20,000 residents were living in the distant suburbs of left-bank Warsaw, while 140,000 lived in the Praga district. Just before the war, Warsaw had a population of 1,289,000.

Despite that grim picture, Warsaw inhabitants returned home. Drawn by hope or stubborn attachment, thousands crossed frozen roads to search for fragments of their former lives. “We knew there was nothing,” wrote one returning resident, “but we had to see it ourselves. A city doesn’t stop being yours just because it’s been destroyed.”

Warsaw’s rebirth would take decades, fuelled by resilience rather than proclamations. And while the word “liberation” still appears in official statements beyond Poland’s borders, many here prefer a harsher, truer phrase: the end of one occupation, and the beginning of another.

For almost the entire period of the Polish People’s Republic, 17 January was an important state holiday; in the Soviet Union, a decree of the Praesidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of 9 June 1945 even established the “Medal for the Liberation of Warsaw”.

This decoration was awarded to an enormous number of soldiers, over 700,000, including soldiers of the 1st Polish Army, the Red Army, as well as members of the NKVD. The date inscribed in Russian, 17 January, left no room for doubt: fighting shoulder to shoulder, Polish and Soviet soldiers, after heroic battles, had “liberated” the capital of Poland.

Because of Poland’s domestic political differences that hamper the process of decomunnization, even today, the day of 17 January is celebrated in the name of one of the main city arteries.

Photo: X/@IPN

Tomasz Modrzejewski